pISSN : 3058-423X eISSN: 3058-4302

Open Access, Peer-reviewed

pISSN : 3058-423X eISSN: 3058-4302

Open Access, Peer-reviewed

Jinkyeong Kim,Sook Jung Yun,Jee-Bum Lee

10.17966/JMI.2022.27.3.51 Epub 2022 October 05

Abstract

Fusarium species are widely distributed throughout the environment, and rarely cause infection in healthy individuals. Herein, we report a rare case of cutaneous infection by Fusarium solani in a healthy patient. A 64-year-old patient presented with a tender, erythematous, deep-seated nodule above the left ankle after an intralesional triamcinolone injection for lipoma was administered at a private clinic 1 month ago. Fungal hyphae were identified in subcutaneous tissue by skin biopsy using Gomori methenamine silver stain. Lactophenol cotton blue staining, fungal culturing, and 28S rRNA sequencing confirmed the presence of F. solani. After diagnosis, the patient was successfully treated with oral itraconazole.

Keywords

Fusarium species are molds that are widely distributed throughout the environment, including soil, air, water, and plants1-3. They generally infect immunocompromised patients, especially those with hematologic malignancy, bone marrow transplantation, and neutropenia2,3. They rarely cause local infections, like septic arthritis, endophthalmitis, osteomyelitis, cystitis, and brain abscess, in immunocompetent patients2. However, they can cause cutaneous infections through skin breakdown by burns, trauma, foreign bodies, or vascular insufficiency2,3.

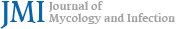

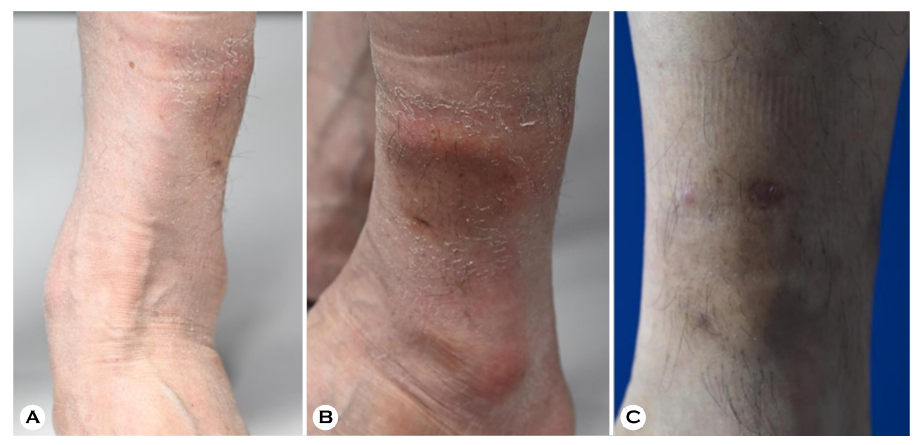

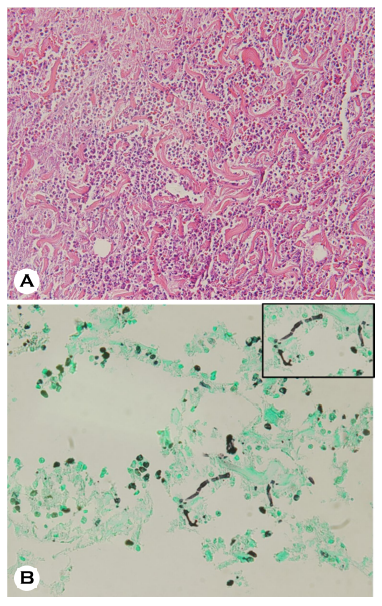

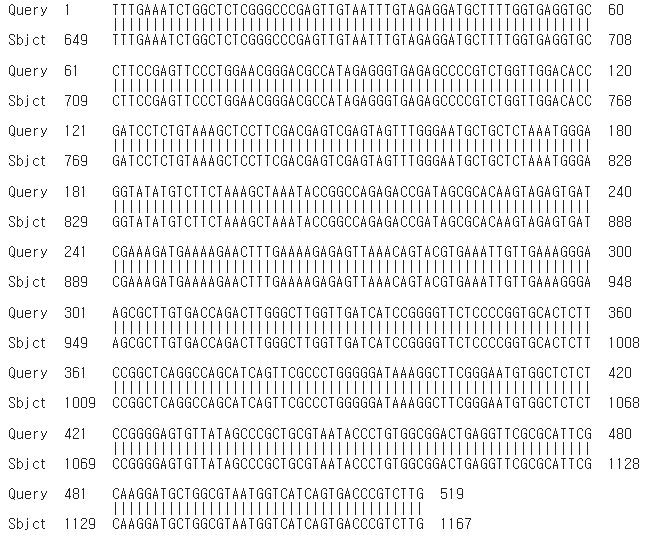

The patient provided written informed consent. The patient was a 64-year-old male presented with a tender, erythematous, deep-seated nodule on the outer aspect above his left ankle. This nodule developed one month after an intralesional triamcinolone injection for lipoma was administered at a private clinic (Fig. 1A, 1B). His vital signs were normal. He had no symptoms except for tenderness above his left ankle. He had no history of skin infection by Fusarium. Laboratory investigations showed that his complete blood cell count, liver function test, and renal function test reports were within the normal range. A skin biopsy was taken from the tender nodule and was stained with Gomori methenamine silver (GMS) stain. Additionally, fungal culture of the skin tissue sample was done on Sabouraud dextrose agar (SDA) plate. Histopathological examination showed dense mixed inflam- matory cells and red blood cell extravasation in deep dermis. Fungal hyphae were observed in subcutaneous tissue stained with GMS stain (Fig. 2). The top view of the colonies obtained on the SDA plate appreared yellow in the center and had white floccose appearance (Fig. 3A). The bottom view of the SDA plate showed yellow-brownish colored colonies (Fig. 3B). Lactophenol cotton blue staining of the culture revealed sickle-shaped macroconidia with three thick septa (Fig. 3C). 28S rRNA sequencing was performed to confirm the fungal species, and the fungal culture was identified as Fusarium solani (Fig. 4). Based on these findings, cutaneous fungal infection by F. solani was diagnosed. The patient was treated with oral itraconazole (200 mg/day) for about 4 months and was completely cured. The patient was followed up for 12 months and showed no clinical signs of recurrence (Fig. 1C).

Fusarium species are widely distributed throughout the environment. They are divided into several species complexes (SC) such as F. solani SC, F. oxysporum SC, F. fujikuroi SC, and F. dimerum SC4. Fusarium infection has rarely been reported in immunocompetent individuals. It shows slower progression in such patients than in immunocompromised patients5. Usually, patients with Fusarium infection have a previous history of infection through skin breakdown5. In this case, cutaneous infection occurred one month after intralesional triamcinolone injection. Therefore, cutaneous fungal infection should be considered even in healthy patients showing slowly progressing skin lesions with previous trauma history such as insect bites or needle injuries. Skin and soft tissue infections develop in approximately 75~90% cases of disseminated Fusarium infection1. According to previous re- ports, the upper and lower extremities are the most common sites. Common morphologic types of skin lesions include red or gray papular and macular type lesions with central eschar and necrosis and subcutaneous nodular type lesions1. Previous studies have reported various skin lesions such as necrotic tissue, cellulitis with necrosis, ulceration, and plaque type with vesicles and pustules in immunocompetent patients. Most of these patients had a history of skin breakdown such as burns, trauma, and preexisting onychomycosis5.

Most Fusarium species are resistant to antifungal agents2,3. In particular, F. solani SC shows high resistance to various antifungal agents6 and has high minimal inhibitory concen- tration to many azoles including posaconazole, itraconazole, and difenoconazole4. The ideal treatment regimen for Fusarium infections is controversial. Combination therapy of liposomal amphotericin B and voriconazole is most commonly used6. However, unlike immunocompromised patients, cases successfully treated by oral itraconazole or local heat therapy have been reported7,8. In this case, the patient was effectively treated with oral itraconazole, and he had no recurrence during the 12-month follow-up period.

References

1. Bodey GP, Boktour M, Mays S, Duvic M, Kontoyiannis D, Hachem R, et al. Skin lesions associated with Fusarium infection. J Am Acad Dermatol 2002;47:659-666

Google Scholar

2. Gupta AK, Baran R, Summerbell RC. Fusarium infections of the skin. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2000;13:121-128

3. Kim HJ, Kim JW, Lee JY, Kim MK, Yoon TY. Cutaneous infection by Fusarium solani associated with arterio- sclerosis obliterans in an immunocompetent patient. Ann Dermatol 2007;19:142-145

Google Scholar

4. Herkert PF, Al-Hatmi AM, de Oliveira Salvador GL, Muro MD, Pinheiro RL, Nucci M, et al. Molecular characterization and antifungal susceptibility of clinical Fusarium species from Brazil. Front Microbiol 2019;10:737

Google Scholar

5. Nucci M, Anaissie E. Cutaneous infection by Fusarium species in healthy and immunocompromised hosts: implications for diagnosis and management. Clin Infect Dis 2002;35:909-920

Google Scholar

6. Taj-Aldeen SJ. Reduced multidrug susceptibility profile is a common feature of opportunistic Fusarium species: Fusarium multi-drug resistant pattern. J Fungi 2017;3: 18

Google Scholar

7. Nakamura Y, Xu X, Saito Y, Tateishi T, Takahashi T, Kawachi Y, et al. Deep cutaneous infection by Fusarium solani in a healthy child: successful treatment with local heat therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007;56:873-877

Google Scholar

8. Lee MH, Yoo JY, Song YB, Suh MK, Ha GY, Lee JI, et al. Localized skin infection caused by Fusarium oxysporum. Korean J Med Mycol 2013;18:70-75

Google Scholar

Congratulatory MessageClick here!