pISSN : 3058-423X eISSN: 3058-4302

Open Access, Peer-reviewed

pISSN : 3058-423X eISSN: 3058-4302

Open Access, Peer-reviewed

Nam Gyoung Ha,Kyung Duck Park,Yong Jun Bang,Jae Bok Jun,Jong Soo Choi,Weon Ju Lee

10.17966/JMI.2021.26.3.72 Epub 2021 October 04

Abstract

Purpureocillium lilacinum is a saprophytic fungus with a ubiquitous environmental distribution, and it can be detected in soil samples and decaying materials worldwide. It has been reported as an emerging pathogen in both immunocompromised and immunocompetent patients, showing various cutaneous presentations. Herein, we report a case of a patient with a localized cutaneous P. lilacinum infection, which resembles the skin lesions of psoriasis. A 72-year-old female was presented with a peripherally spreading, well-demarcated, asymptomatic, scaly, erythematous patch on her forehead for several months. Histopathological examination showed pinkish septated fungal elements and mixed inflammatory and granulomatous infiltrates in the dermis. Furthermore, a fungal culture on potato dextrose agar showed gray, velvety colonies with light yellow background after being subcultured. Phialides with chains of oval conidia were observed on lactophenol cotton blue staining. The ITS region of rRNA gene sequence obtained from the colony was identical to that of Purpureocillium lilacinum. The lesion was resolved with oral itraconazole (200 mg/day) after four months of treatment.

Keywords

Cutaneous infection Psoriasis Purpureocillium lilacinum

Purpureocillium lilacinum, which was previously known as Paecilomyces lilacinus, is a ubiquitous, saprobic filamentous fungus commonly isolated from soil, decaying vegetation, insects, nematodes, and laboratory air (as a contaminant)1. In recent studies, it has been reported as an emerging patho- gen in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised patients2, commonly causing ocular and subcutaneous infections3. Cutaneous P. lilacinum infections have various clinical manifestations, such as small erythematous papules, plaques with central umbilication, or hemorrhagic vesicles or ulcerations4. However, no standard antifungal treatment regimen has been established, so several systemic antifungal agents and surgical excision are used5,6. Herein, we encountered a rare case of cutaneous P. lilacinum infection, which resembles the skin lesions of psoriasis in a healthy immunocompetent patient.

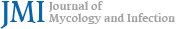

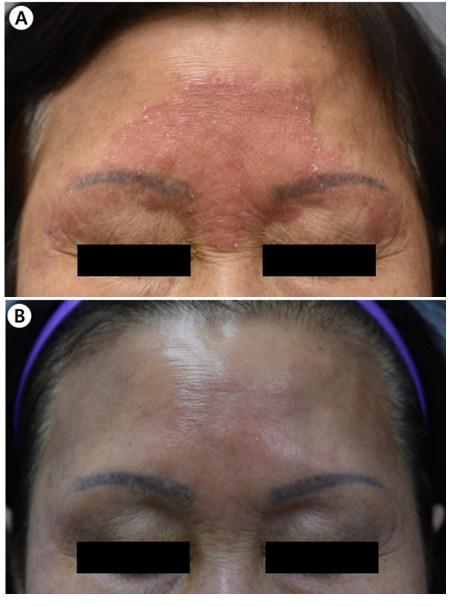

A 72-year-old female was presented with a peripherally spreading, well-demarcated, asymptomatic, scaly, erythema- tous patch on her forehead for several months (Fig. 1A). The patient was not immunocompromised, and laboratory test results, including complete blood count and blood chemistry, were within the normal range. She was diagnosed with psoriasis and tinea faciei on her first hospital visit. Although she was treated with oral steroid and anti-histamine medication and topical steroid for three weeks for psoriasis, her skin lesions did not improve. Fungal culture, lactophenol cotton blue staining, skin biopsy, and ribosomal RNA (rRNA) sequencing were done. The fungal culture on potato dextrose agar showed gray, velvety colonies with light yellow background after being subcultured (Fig. 2A). Phialides with chains of oval conidia were observed on lactophenol cotton blue staining (Fig. 2B). Periodic acid-Schiff with diastase (D-PAS) staining revealed pinkish septated fungal elements and mixed inflam- matory and granulomatous infiltrate in the dermis (Fig. 2C). Based on sequence analysis of the internal transcribed spacer region of rRNA gene, P. lilacinum (Table 1) was identified using the GenBank Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST). The

GenBank BLAST search revealed 100% (963/963 bp) similarity with 126 P. lilacinum strains. Therefore, the final diagnosis was cutaneous P. lilacinum infection. The patient was treated with oral itraconazole (200 mg/day) for four months. Most of the skin lesions were improved after 16 weeks of treatment (Fig. 1B).

|

ITS sequence |

|

ATCATTACCGAGTTATACAACTCCCAAACCCACTGTGAACCTTACCTCA-GTTGCCTCGGCGGGAACGCCCCGGCCGCCTGCCCC

CGCGCCGGCGCCGGACCCAGGCGCCCGCCGCAGGGACCCCAAACTCTCTTGCA-TTACGCCCAGCGGGCGGAATTTCTTCTCT

GAGTTGCACAAGCAAAAACAAATGAATCAAAACTTTCAACAACGGATCTCTTGGTTCTGGCATCGATGAAGAACGCAGCGAAATGCGATAAGTAATGTGAATTGCAGAATTCAGTGAATCATCGAATCTTTGAACGCACATTGCGCCCGCCAGCATTCTGGCGGGCATGCCTGTTCGAGCGTCATTTCAACCCTCGAGCCCCCCCGGGGGCCTCGGTGTTGGGGGACGGCACACCAGCCGCCCCCGAAATGCAGTGGCGACCCCGCCGCAGCCTCCCCTGCGTAGTAGCACACACCTCGCACCGGAGCGCGGAGGCGGTCACGCCGTAAAACGCCCAACTTTCTTAGAGTTGACC. |

P. lilacinum is a fungal pathogen found in soil and decaying vegetation. Although P. lilacinum infections primarily occur in immunocompromised patients, it is considered an emerging disease in immunocompetent patients as well8. Skin infections caused by P. lilacinum are very rare, and only eight cases have been reported in Korean literature (Table 2)9-16. The present case was a case of cutaneous P. lilacinum infection in an immunocompetent patient who was initially diagnosed with psoriasis and tinea faciei.

The predisposing factors of cutaneous P. lilacinum infec- tions are malignancy, solid and bone marrow transplantation, long-term glucocorticoid use, and other immunosuppressed conditions4; however, several cases occurring in immuno- competent patients have also been reported. Among the 42 reported cases of cutaneous and subcutaneous P. lilacinum infections reported in Korean journals from 1977 to 2004, eight cases (18.6%) had no predisposing factors8. Furthermore, six of the eight (75.0%) patients showed no risk factors for infection, and seven of the eight (87.5%) patients were immunocompetent. Interestingly, the average age of the eight patients was 69.2±22.4 years old, and six of the eight (75.0%) patients were older than 70 years old, which implies that old age possibly has a significant relationship with cutaneous P. lilacinum infections. In this case, the patient was a 72-year-old healthy woman who had no underlying diseases and medication history that would suggest an immunocompetent status.

Cutaneous P. lilacinum infections could manifest clinically as various skin lesions, such as patches, plaques, vesicles, pustules, nodules, and crusts7. This infection primarily involves exposed areas, such as the face, arms, and legs14. Among the eight patients reported in Korean journals, seven cases had lesions in the upper extremities, including the hand, forearm, and shoulder, and one experienced a clear preceding trauma. Only one out of the eight cases had a lesion involving the face. Our patient showed a well-demarcated erythematous scaly patch on the forehead, and this cutaneous finding led to the initial diagnosis of psoriasis and tinea faciei. After the treatment failure for these diagnoses, fungal cultures, histologic studies, and rRNA gene sequencing were conducted, and the diag- nosis of cutaneous P. lilacinum infection was confirmed.

The standard treatment for cutaneous P. lilacinum infections is not yet established, and the treatment is often challenging8. This fungus is highly resistant to conventional antifungal agents, including amphotericin B, fluconazole, and flucytosine, and the results of its in vitro susceptibility tests to itraconazole are conflicting17,18. In contrast, terbinafine or triazole antifungal agents, such as voriconazole, ravuconazole, and posaconazole, broadly showed a low level of minimum inhibitory concen- tration based on their in vitro susceptibility tests14. In the cases reviewed here, including the present case, five patients were successfully treated with itraconazole monotherapy and improved clinically, whereas two patients who showed resistance to this treatment required a combination therapy with voriconazole and terbinafine, respectively11-16. One patient was treated with ketoconazole combined with griseofulvin9, and one patient was treated with skin lesion excision10.

Briefly, we report a case of a localized cutaneous P. lilacinum infection in a healthy patient with no underlying diseases and with clinical manifestations similar to psoriasis. Thus, it is important to suspect this atypical and rare fungal infection when a patient shows a poor treatment response. This study also provides a literature review of cutaneous fungal infections caused by P. lilacinum in Korea.

|

Author |

Age/ |

Cutaneous |

Location |

Immune status |

Predisposing |

Treatment |

|

Cho et al.9 |

19/M |

Erythematous patch |

Cheek |

Immunocompetent |

None |

Griseofulvin, |

|

Shin et al.10 |

46/M |

Erythematous nodules |

Forearm |

Immunocompromised |

Renal |

Excision |

|

Ko et al.11 |

83/M |

Erythematous plaque |

Wrist |

Immunocompetent |

None |

Itraconazole |

|

Hwang et al.12 |

81/M |

Erythematous plaque |

Hand |

Immunocompetent |

None |

Itraconazole |

|

Jung et al.13 |

72/M |

Erythematous plaque |

Shoulder |

Immunocompetent |

None |

Itraconazole, |

|

Kwak et al.14 |

81/M |

Erythematous |

Dorsal |

Immunocompetent |

None |

Itraconazole |

|

Kim et al.15 |

85/F |

Erythematous plaque |

Forearm, |

Immunocompetent |

None |

Itraconazole, Terbinafine |

|

Jung et al.16 |

84/M |

Erythematous papules |

Forearm |

Immunocompetent |

Injury from hoe |

Itraconazole |

|

Present case |

72/F |

Erythematous patch |

Forehead |

Immunocompetent |

None |

Itraconazole |

References

1. Luangsa-Ard J, Houbraken J, van Doorn T, Hong SB, Borman AM, Hywel-Jones NL, et al. Purpureocillium, a new genus for the medically important Paecilomyces lilacinus. FEMS Microbiol Lett 2011;321:141-149

Google Scholar

2. Accetta J, Powell E, Boh E, Bull L, Kadi A, Luk A. Isavu- conazonium for the treatment of Purpureocillium lilacinum infection in a patient with pyoderma gangrenosum. Med Mycol Case Rep 2020;29:18-21

Google Scholar

3. Salazar-González MA, Violante-Cumpa JR, Alfaro-Rivera CG, Villanueva-Lozano H, Treviño-Rangel RJ, González GM. Purpureocillium lilacinum as unusual cause of pulmonary infection in immunocompromised hosts. J Infect Dev Ctries 2020;14:415-419

Google Scholar

4. Chen WY, Lin SR, Hung SJ. Successful treatment of recur- rent cutaneous Purpureocillium lilacinum (Paecilomyces lilacinus) infection with posaconazole and surgical de- bridement. Acta Derm Venereol 2019;99:1313-1314

Google Scholar

5. Saghrouni F, Saidi W, Said ZB, Gheith S, Said MB, Ranque S, et al. Cutaneous hyalohyphomycosis caused by Pur- pureocillium lilacinum in an immunocompetent patient: case report and review. Med Mycol 2013;51:664-668

Google Scholar

6. Hall VC, Goyal S, Davis MD, Walsh JS. Cutaneous hyalohyphomycosis caused by Paecilomyces lilacinus : report of three cases and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol 2004;43:648-653

Google Scholar

7. Itin PH, Frei R, Lautenschlager S, Buechner SA, Surber C, Gratwohl A, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of Paecilo- myces lilacinus infection induced by a contaminated skin lotion in patients who are severely immunosuppressed. J Am Acad Dermatol 1998;39:401-409

8. Pastor FJ, Guarro J. Clinical manifestations, treatment and outcome of Paecilomyces lilacinus infections. Clin Microbiol Infect 2006;12:948-960

Google Scholar

9. Cho GY, Choo EH, Choi GJ, Hong NS, Houh W. Facial cutaneous mycosis by Paecilomyces lilacinus. Korean J Dermatol 1984;22:89-93

Google Scholar

10. Shin SB, Lee HN, Kim SW, Park GS, Cho BK, Kim HJ. Cutaneous abscess caused by Paecilomyces lilacinus in a renal transplant patient. Korean J Med Mycol 1998;3: 185-189

Google Scholar

11. Ko WT, Kim SH, Suh MK, Ha GY, Kim JR. A case of localized skin infection due to Paecilomyces lilacinus. Korean J Dermatol 2007;45:930-933

Google Scholar

12. Hwang SL, Kim JI, Song KH, Cho YS, Nam GH, Park J, et al. A localized skin infection due to Paecilomyces lilacinus. Korean J Dermatol 2011;64(Suppl. 1):255

Google Scholar

13. Jung MY, Park JH, Lee JH, Lee JH, Yang JM, Lee DY. A localized cutaneous Paecilomyces lilacinus infection treated with voriconazole. Korean J Dermatol 2013;51: 833-836

Google Scholar

14. Kwak HB, Park SK, Yun SK, Kim HU, Park J. A case of localized skin infection due to Paecilomyces lilacinum. Korean J Med Mycol 2017;22:42-49

Google Scholar

15. Kim HJ, Cho GJ, Kim JU, Jin WJ, Park SH, Moon SH, et al. A case of deep cutaneous Purpureocillium lilacinum fungal infection in an immunocompetent patient. J Mycol Infect 2019;24:52-57

Google Scholar

16. Jung ES, Lee SK, Lee IJ, Park J, Yun SK, Kim HU. A case of cutaneous Purpureocillium lilacinum infection. J Mycol Infect 2021;26:8-12

Google Scholar

17. Aguilar C, Pujol I, Sala J, Guarro J. Antifungal susceptibilities of Paecilomyces species. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1998;42:1601-1604

Google Scholar

18. Castelli MV, Alastruey-Izquierdo A, Cuesta I, Monzon A, Mellado E, Rodriguez-Tudela JL, et al. Susceptibility testing and molecular classification of Paecilomyces spp. Anti- microb Agents Chemother 2008;52:2926-2928

Google Scholar

Congratulatory MessageClick here!