pISSN : 3058-423X eISSN: 3058-4302

Open Access, Peer-reviewed

pISSN : 3058-423X eISSN: 3058-4302

Open Access, Peer-reviewed

Bo Young Moon,Jong Soo Choi,Dong Hoon Shin,Joon Goon Kim,Jae Bok Jun,Young Jun Bang,Jin Park,Seun Kang,Jahyeon Sim,Kyung-Tae Lee

10.17966/JMI.2025.30.4.154 Epub 2026 January 01

Abstract

Trichophyton indotineae is an emerging terbinafine-resistant dermatophyte within the T. mentagrophytes / T. interdigitale complex. Herein, we describe the first two confirmed Korean cases of T. indotineae infection. Both patients had chronic and extensive dermatophytosis involving the trunk, buttocks, thighs, and groin in case 1 and confined to the right lower leg and ankle in case 2. In both cases, the eruption failed to respond to terbinafine or itraconazole and was aggravated by intermittent corticosteroid use. Cultures produced white cottony colonies with grape-like microconidia and negative urease reactions. Internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region sequencing identified T. indotineae, and analysis of the squalene epoxidase (SQLE) gene showed L393F mutation, which was associated with terbinafine resistance. Antifungal susceptibility testing revealed terbinafine resistance but susceptibility to itraconazole. After withdrawal of corticosteroids and maintenance of continuous itraconazole therapy, case 1 showed near-complete clinical remission with minimal residual scaling, whereas case 2 achieved complete clinical and mycological remission. These findings suggest possible local transmission and emphasize the importance of molecular confirmation and antifungal stewardship in Korea.

Keywords

Antifungal susceptibility Dermatophyte Korea Squalene epoxidase Terbinafine resistance Trichophyton indotineae

In 2020, Trichophyton indotineae was recognized as a distinct species within the TMTI complex after characterization of the highly terbinafine-resistant genotype VIII1. Since 2018, an epidemic-like increase in recalcitrant dermatophytosis has been documented in India, which was largely attributed to the inappropriate use of topical steroid-antifungal combinations and incomplete antifungal therapy2,3. Following its initial description, T. indotineae has been reported across Asia, the Middle East, Europe, and North America4-7. By 2024-2025, confirmed cases of T. indotineae had also emerged in Taiwan and Thailand8,9.

In Korea, clinicians have increasingly suspected terbinafine-resistant dermatophytosis. However, to date, no infections had been molecularly confirmed as T. indotineae. Herein, we report two such cases and discuss their clinical course, laboratory confirmation, and implications for local transmission and antifungal stewardship.

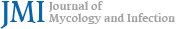

A 36-year-old man presented with multiple pruritic plaques involving the trunk, buttocks, and legs that had persisted for more than one year. The eruption began as small erythema- tous annular plaques on the thighs and gradually expanded, forming large confluent scaly plaques (Fig. 1, A1 and A2). The patient had been treated with topical terbinafine preparation and oral terbinafine (200-375 mg/day) for three months with- out improvement. In fact, the lesions became more extensive. Subsequently, he received oral itraconazole (200 mg/day) irregularly for about five months. However, this regimen only led to brief periods of partial improvement. For severe itching, he intermittently received short courses of oral methylpredni- solone and used topical antifungal-corticosteroid combination creams (clotrimazole-hydrocortisone, econazole-triamcinolone acetonide, and isoconazole nitrate-diflucortolone valerate), but the eruption progressively worsened. The patient had no history of overseas travel.

Several months after his eruption began, his Korean partner developed similar pruritic annular plaques, raising suspicion of household transmission. A 29-year-old woman presented with large coalescent annular plaques on her right ankle and lower leg, accompanied by intense pruritus and excoriations (Fig. 1, B1). She had taken oral terbinafine (250 mg/day) for three months without significant response. Subsequent treat- ment with oral itraconazole (200 mg/day) for five months, together with the same topical antifungal-corticosteroid com- bination creams as case 1 and intermittent short courses of oral methyl-prednisolone, produced only transient relief. Moreover, the affected area slowly enlarged during this period. The patient also denied any travel abroad.

In both patients, the lack of response to an apparently adequate course of oral terbinafine raised strong suspicion for terbinafine-resistant dermatophytosis. Irregular itracona- zole therapy combined with the intermittent use of cortico- steroids did not induce remission. Therefore, all topical and systemic corticosteroids were discontinued, and itraconazole was switched to another generic formulation and administered at 200 mg/day under close supervision. Both patients steadily improved with strict adherence to this regimen. After five months, case 2 showed complete clinical and mycological remission, whereas case 1 showed near-complete clearance with only faint residual scaling on the buttocks and thighs (Fig. 1, A3, A4, and B2). Follow-up cultures were negative in both cases, although a few hyphae were still detectable on direct KOH examination in case 1.

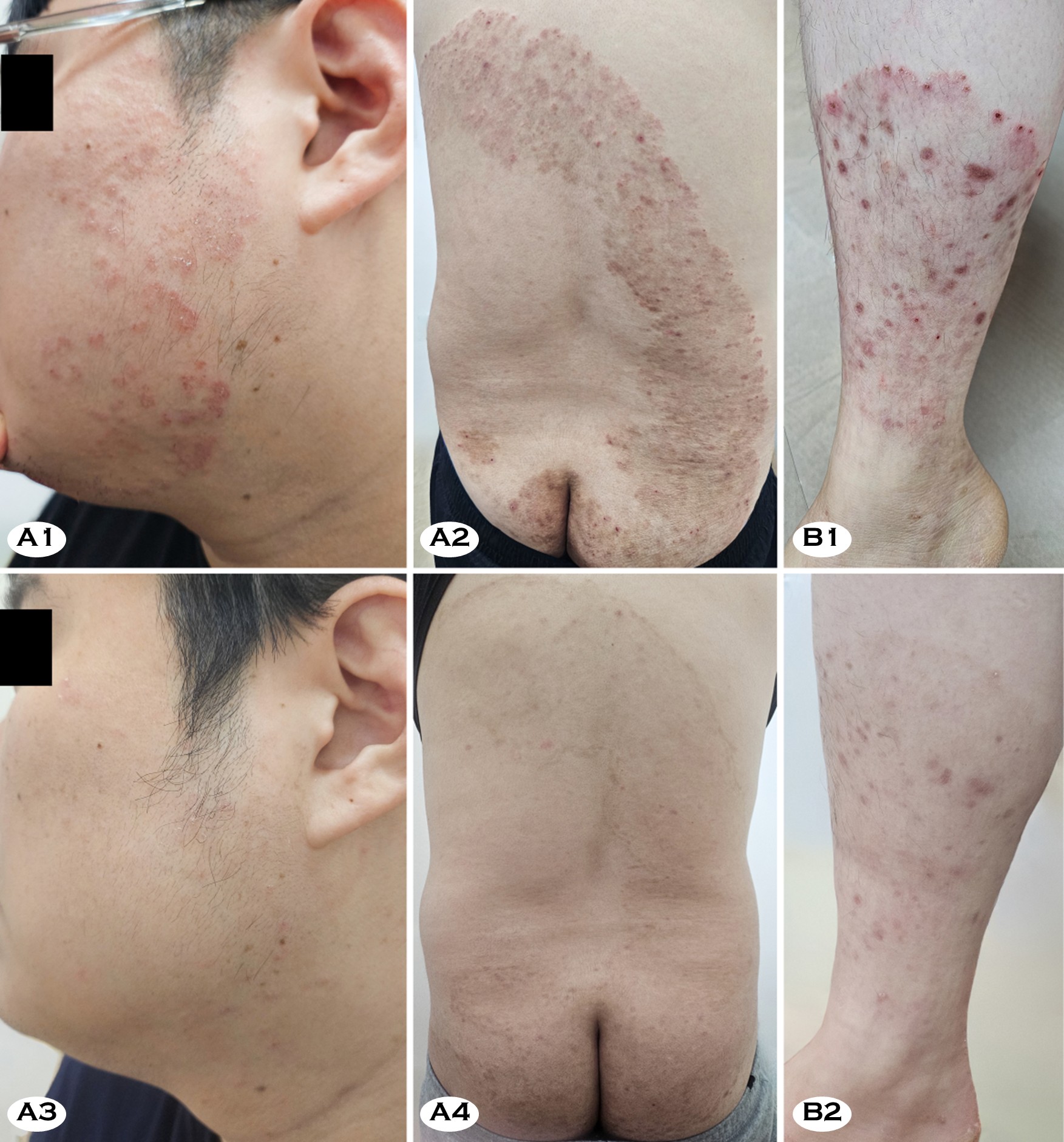

Direct KOH examination of skin scraps from both patients revealed branching septate hyphae. Meanwhile, cultures on Sabouraud dextrose agar and potato dextrose cornmeal agar with Tween 80, incubated at 25-30℃, produced colonies within 10 days. The colonies were white to gray in color, fluffy, and somewhat cottony with yellow-brown reverse pigmentation (Fig. 2, A and B).

Microscopic examination revealed numerous pyriform microconidia arranged in grape-like clusters, spiral hyphae, and frequent macroconidia, which are features compatible with the TMTI complex (Fig. 2, C and D). Urease test on Christensen's urea agar remained negative after 14 days, whereas T. mentagrophytes and T. interdigitale controls typic- ally became positive within one week (Fig. 2, E). The negative urease reaction supported T. indotineae as the presumptive species.

DNA sequencing of the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region showed 100% identity with the T. indotineae type strains NUBS19006 (NR_173767) and NUBS19007 (LC- 508728). Meanwhile, squalene epoxidase (SQLE) gene se- quencing identified a c.1179A>T substitution at codon 393, resulting in the L393F amino acid change.

Antifungal susceptibility testing was performed according to the CLSI M38-A3 protocol. The minimum inhibitory con- centrations (MICs) are summarized in Table 1. Both isolates demonstrated high-level resistance to terbinafine (MIC values >10 μg/mL) while remaining susceptible to itraconazole and posaconazole.

|

Antifungal agents§ |

Case 1 |

Case 2 |

|

TBF |

10.67 |

25.33 |

|

KCZ |

0.54 |

0.54 |

|

MCZ |

0.58 |

1.02 |

|

CTZ |

1.67 |

3.33 |

|

ICZ |

0.07 |

0.08 |

|

FCZ |

49.00 |

96.00 |

|

VCZ |

0.46 |

0.54 |

|

PSC |

0.06 |

0.21 |

|

IVZ |

4.17 |

4.00 |

|

AmB |

0.13 |

0.06 |

|

GRF |

0.54 |

0.58 |

|

§Abbreviations: AmB, amphotericin B; CTZ, clotrimazole; FCZ,

fluconazole; GRF, griseofulvin; ICZ, itraconazole; IVZ, isavuconazole; KCZ,

ketoconazole; MCZ, miconazole; PSC, posaconazole; TBF, terbinafine; VCZ,

voriconazole |

||

These two cases represent the first molecularly confirmed T. indotineae infections acquired in Korea. The lack of travel history in both patients and the occurrence of a similar eruption in a household contact of case 1 suggest that an imported terbinafine-resistant strain may now be circulating domestically, as has been observed in other regions5,6,9.

Morphologic differentiation among members of the TMTI complex is difficult and often unreliable10. In our patients, the colony morphology and microscopic findings were compatible with the TMTI complex, but not distinctive for T. indotineae. The negative urease tests raised suspicion, whereas definitive identification required ITS sequencing. This finding highlights the need for access to molecular tools and updated matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight databases or species-specific polymerase chain reaction assays, where available7,11.

Terbinafine resistance in T. indotineae has been associated with structural alterations in SQLE that reduce terbinafine binding while preserving enzyme function. The F397L sub- stitution is most frequently reported worldwide, followed by L393F, with other substitutions being less commonly described7,10,12. Our isolates carried L393F and showed high terbinafine MICs, consistent with these reports.

Clinicians should consider T. indotineae when patients present with large, scaly plaques involving the trunk and groin while sparing the feet and nails, and fail to respond to a 4~6-week course of appropriately dosed terbinafine3,13,14. A negative urease test in a TMTI-complex isolate further raises suspicion for this species10. In such cases, mycological con- firmation, including culture, molecular identification, and antifungal susceptibility testing, is important for patient man- agement and surveillance7,11.

Itraconazole is generally effective against T. indotineae. However, clinical outcomes may be compromised by irregular intake, suboptimal formulations, or concurrent corticosteroid use14,15. In our patients, in vitro susceptibility testing suggested that itraconazole remained active, and clinical failure appeared to be driven primarily by irregular dosing, concomitant use of systemic and topical corticosteroids, and possibly formulation-dependent differences among itraconazole generics. Both patients showed gradual but sustained improvement under supervised itraconazole monotherapy at 200 mg/day with complete withdrawal of corticosteroids, resulting in near-complete clearance with minimal residual scaling and low-level residual hyphae on KOH in case 1 and complete clinical and mycological remission in case 2. Because therapeutic drug monitoring was not performed, our experience cannot be taken as proof of superiority of one generic over another. However, the temporal association suggests that formulation-dependent bioavailability and consistent intake may play a clinically relevant role in real-world practice15.

For symptom control, patients with severe pruritus are often prescribed with short courses of topical or systemic cortico- steroids. However, in active dermatophytosis, corticosteroids can modify lesion morphology, delay diagnosis, and prolong the disease course2,3,13. During antifungal therapy, symptom- atic relief should primarily rely on nonsteroidal measures, including oral antihistamines, emollients, and cooling agents. If corticosteroids are considered unavoidable, they should be used at the lowest effective potency and for the shortest possible duration under close follow-up.

From a public health standpoint, the emergence of T. indotineae in Korea highlights the need for coordinated anti- fungal resistance surveillance. In Europe, reference laboratory networks and standardized susceptibility testing have enabled earlier recognition of resistant dermatophytes4,16. However, antifungal susceptibility testing is rarely performed in routine practice in Korea, largely because it is not reimbursed. The inclusion of such testing within insurance coverage, together with national guidelines recommending when to test, would facilitate systematic monitoring of MIC trends and SQLE mutations. Ongoing data collection will be essential for up- dating treatment recommendations and supporting antifungal stewardship.

This report is limited by the small number of patients, lack of therapeutic drug monitoring for itraconazole, and absence of confirmatory testing in household contacts. Moreover, although case 2 achieved complete clinical and mycological cure, case 1 still showed minimal residual scaling and a few hyphae on KOH at the last follow-up. Therefore, longer observation is needed to confirm durable mycological cure. Our statement that these are the first molecularly confirmed T. indotineae cases in Korea is based on extensive searches of domestic and international literature and conference abstracts available at the time of writing. However, unpublished or unrecognized cases may exist.

T. indotineae has now been identified as a terbinafine-resistant dermatophyte causing extensive tinea corporis and cruris in Korea. This species should be suspected when large, intensely pruritic plaques on the trunk and groin persist des- pite standard terbinafine therapy and when urease-negative isolates of the TMTI complex are recovered. Corticosteroid withdrawal, use of adequately dosed itraconazole, and access to molecular identification and antifungal susceptibility testing will be crucial to treat and limit the spread of T. indotineae.

References

1. Kano R, Kimura U, Kakurai M, Hiruma J, Kamata H, Suga Y, et al. Trichophyton indotineae sp. nov.: A new highly terbinafine-resistant anthropophilic dermatophyte species. Mycopathologia 2020;185:947-958

Google Scholar

2. Nenoff P, Verma SB, Uhrlaß S, Burmester A, Gräser Y. A clarion call for preventing taxonomical errors of dermato- phytes using the example of the novel Trichophyton mentagrophytes genotype VIII uniformly isolated in the Indian epidemic of superficial dermatophytosis. Mycoses 2019;62:6-10

Google Scholar

3. Verma SB, Panda S, Nenoff P, Singal A, Rudramurthy SM, Uhrlass S, et al. The unprecedented epidemic-like scenario of dermatophytosis in India: I. Epidemiology, risk factors and clinical features. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2021;87:154-175

Google Scholar

4. Lockhart SR, Smith DJ, Gold JAW. Trichophyton indotineae and other terbinafine resistant dermatophytes in North America. J Clin Microbiol 2023;61:e0090323

Google Scholar

5. Caplan AS, Todd GC, Zhu Y, Sikora M, Akoh CC, Jakus J, et al. Clinical course, antifungal susceptibility, and geno- mic sequencing of Trichophyton indotineae. JAMA Dermatol 2024;160:701

Google Scholar

6. Er YX, Leong KF, Foong HBB, Abdul Halim AA, Kok JS, Yap NJ, et al. Dermatophytoses caused by Trichophyton indotineae: The first case reports in Malaysia and the global epidemiology (2018-2025). J Fungi 2025;11:523

Google Scholar

7. Xie W, Liang G, Kong X, Tsui CKM, She X, Liu W, et al. Genomic epidemiology and antifungal resistance of emerging Trichophyton indotineae in China. Emerg Microbes Infect 2025;14:2498571

Google Scholar

8. Prunglumpoo S, Krongboon K, Intarachaieua K, Kazushi A, Bunnag T, Paunrat W, et al. Emergence of resistant dermatophytosis caused by Trichophyton indotineae: First case series in Thailand. Med Mycol Case Rep 2025;48: 100713

Google Scholar

9. Wang HT, Li ML, Wu WL, Wu CJ, Liu WT. Emergence of terbinafine-resistant Trichophyton indotineae dermato- phytosis in a familial cluster in Taiwan: Successful man- agement with prolonged oral itraconazole. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 2025;S1684-1182(25)00138-0

Google Scholar

10. Tan TY, Wang YS, Wong XYA, Rajandran P, Tan MG, Tan AL, et al. First reported case of Trichophyton indotineae dermatophytosis in Singapore. Pathology 2024;56:909-913

Google Scholar

11. Baron A, Hamane S, Gits-Muselli M, Legendre L, Benderdouche M, Mingui A, et al. Dual quantitative PCR assays for the rapid detection of Trichophyton indotineae from clinical samples. Med Mycol 2024;62:myae067

Google Scholar

12. Singh A, Masih A, Khurana A, Singh PK, Gupta M, Hagen F, et al. High terbinafine resistance in Trichophyton interdigitale isolates in Delhi, India harbouring mutations in the squalene epoxidase gene. Mycoses 2018;61:477-484

Google Scholar

13. Uhrlaß S, Verma SB, Gräser Y, Rezaei-Matehkolaei A, Hatami M, Schaller M, et al. Trichophyton indotineae—An emerging pathogen causing recalcitrant dermato- phytoses in India and worldwide—A multidimensional perspective. J Fungi 2022;8:757

Google Scholar

14. Gupta AK, Venkataraman M, Hall DC, Cooper EA, Summerbell RC. The emergence of Trichophyton indo- tineae: Implications for clinical practice. Int J Dermatol 2023;62:857-861

Google Scholar

15. Sehgal IS, Vinay K, Dhooria S, Muthu V, Prasad KT, Aggarwal AN, et al. Efficacy of generic forms of itracona- zole capsule in treating subjects with chronic pulmonary aspergillosis. Mycoses 2023;66:576-584

Google Scholar

16. Arendrup MC, Friberg N, Mares M, Kahlmeter G, Meletiadis J, Guinea J, et al. How to interpret MICs of antifungal compounds according to the revised clinical breakpoints v. 10.0 European committee on antimicrobial susceptibility testing (EUCAST). Clin Microbiol Infect 2020;26:1464-1472

Google Scholar

Congratulatory MessageClick here!