pISSN : 3058-423X eISSN: 3058-4302

Open Access, Peer-reviewed

pISSN : 3058-423X eISSN: 3058-4302

Open Access, Peer-reviewed

Anitha Kalyanasundaram,P Sankari,Riyas khan M,R Saraswathi

10.17966/JMI.2025.30.4.134 Epub 2026 January 01

Abstract

Background: Despite continuous discussions regarding the accuracy of the Widal test, typhoid fever is still a major public health concern in developing nations wherein it is frequently diagnosed.

Objective: This study aimed to investigate the distribution of antibody titers and assess the pattern of Widal test results in the clinically suspected cases of typhoid fever.

Methods: This cross-sectional study included 400 cases of clinically suspected cases of typhoid fever. The O, H, AH, and BH antigens at different dilutions were assessed based on the results of the Widal test, which was performed using the conventional tube agglutination method.

Results: Of the 400 cases (213 females, 187 males), 86 (21.5%) showed positive Widal test results, while 314 (78.5%) showed negative Widal test results. Of the positive cases, 58 cases (67.4%) had isolated O antigen elevation (titer ≥ 1:320), 11 cases (12.8%) had combined O and H elevation (both ≥ 1:320), 1 case (1.2%) had O:320 with H:160, and 1 case (1.2%) had complete reactivity (O, H, AH, and BH; all ≥ 1:320). No discernible gender bias in the male-to-female ratio of 1:1.14 was observed.

Conclusion: The majority of the cases of isolated O antigen elevation are often attributed to either cross-reactivity with other Salmonella species or early infection. In endemic areas, the low overall positivity rate (21.5%) emphasizes the necessity of additional diagnostic techniques in addition to Widal testing.

Keywords

Antibody titers Salmonella typhi Serological diagnosis Widal test typhoid

Typhoid fever, caused by the serovar Typhi of Salmonella enterica, continues to be a serious global health concern, particularly in developing nations with inadequate water supply and sanitation systems. Based on the WHO estimates, 11-20 million cases occur worldwide each year, with South and Southeast Asia bearing the major burden1,2. In India, typhoid fever remains endemic and associated with high morbidity and mortality, especially in rural areas and urban slums wherein sanitation infrastructure is poor3,4.

The nonspecific clinical presentation of typhoid fever and the limitations of current diagnostic methods make it chal- lenging to achieve an accurate diagnosis. Although blood culture remains the gold standard for its diagnosis, its sensitivity ranges from 40% to 80%, and it also requires advanced laboratory facilities and trained personnel5,6. The Widal test, developed by Georges-Fernand Widal in 1896, has been widely used in resource-limited settings because it is simple and cost-effective7,8. It detects agglutinating antibodies against the somatic (O) and flagellar (H) antigens of S. Typhi and the AH and BH antigens of S. Paratyphi9.

However, the test's accuracy is limited by variable sensitivity and specificity, cross-reactivity with other infections, and the difficulty of interpreting titers in endemic areas wherein baseline antibodies are often increased due to prior exposure or vaccination10,11. Indian studies have reported sensitivities of 60-90% and specificities of 70-95,13, but the absence of the standardized regional cutoff values further complicates the interpretation14,15.

Aim of the Study: This study aimed to investigate the dis- tribution of Widal antibody titers and analyze the serological patterns in clinically suspected cases of typhoid fever, contri- buting to the improved interpretation of this test in endemic settings.

1. Study design and setting

A cross-sectional observational study was performed with a study period of 1 year in the Department of Microbiology, Trichy SRM Medical College Hospital and Research Center. The study approval was obtained from the institutional ethics committee, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants or their guardians prior to the study.

2. Study population

This study included a total of 400 patients presenting with symptoms suggestive of typhoid fever, such as prolonged fever (>3 days), headache, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea or constipation, and malaise. The patients who had received antibiotics within the previous 48 hours were ex- cluded. Clinical suspicion was based on the attending clinician's evaluation following the standard WHO case definitions for enteric fever, including persistent fever and the absence of localizing symptoms.

3. Sample collection and processing

The venous blood samples were collected aseptically, and the serum was separated for serological testing. Due to financial and logistic constraints, blood culture and PCR con- firmation were not performed. Thus, the results represented serological, nonculture–confirmed findings.

4. Widal test procedure

The conventional tube agglutination method was used with commercially available antigen suspensions (Tulip Diagnostics Ltd., India). The serum samples were serially diluted from 1:20 to 1:640 using normal saline. Equal volumes of specific antigens—TO (S. Typhi O), TH (S. Typhi H), AH (S. Paratyphi A-H), and BH (S. Paratyphi B-H)—were added to the respective tubes. After incubation at a temperature of 37℃ for 4 hours, agglutination was visually assessed. The endpoint titer was defined as the highest dilution showing visible agglutination.

5. Interpretation criteria

Based on regional laboratory practice and published studies5,12,14, a titer of ≥ 1:160 for both the O and H anti- gens was considered significant, while a titer of ≥ 1:320 was regarded as strongly suggestive of recent infection. Titers of ≥ 1:160 for the AH and BH antigens were considered indicative of possible paratyphoid infection.

6. Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 21.0. Descriptive statistics were used for the demographic characteristics and test results. The categorical variables were expressed as fre- quencies and percentages, while the continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation or median with interquartile range. Normally distributed continuous data were compared using Student's t-test, while the nonparametric data were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test. More- over, categorical comparisons were performed using the chi-square test or Fisher's exact test. Furthermore, statistical significance was set at a p value of < 0.05.

This study included a total of 400 patients with clinically suspected typhoid fever. The male-to-female ratio was 1:1.14, comprising 187 males (46.75%) and 213 females (53.25%). The median age of the study population was 28 years, with the age range extending from 6 months to 75 years.

1. Gender distribution of the positive cases (Table 1)

|

Gende |

Total samples tested |

Positive cases (n) |

Percentage among positives |

|

Male |

187 |

39 |

45.3% |

|

Female |

213 |

47 |

54.7% |

Of the 86 Widal-positive cases, 39 (45.3%) were males and 47 (54.7%) were females. The overall positivity rate was 20.9% (39/187) in males and 22.1% (47/213) in females. The statistical analysis revealed no significant gender pre- disposition (χ2 = 0.078; p = 0.78; 95% CI, 0.62-1.08). The odds ratio for Widal positivity in the females compared with the males was 1.07 (95% CI, 0.64-1.79), indicating no signifi- cant correlation between gender and Widal test positivity.

2. Age distribution analysis (Table 2)

|

Age

group |

Number

of positive cases |

Positives |

Number

of negative cases |

Negatives |

|

<

20 |

20 |

23.3% |

88 |

28.0% |

|

21-40 |

33 |

38.4% |

120 |

38.2% |

|

41-60 |

23 |

26.7% |

88 |

28.0% |

|

>

60 |

10 |

11.6% |

18 |

5.8% |

|

Total |

86 |

100% |

314 |

100% |

The mean age of the negative cases was 29.8 ± 16.4 years, while that of the positive cases was 31.2 ± 18.6 years, in- dicating no statistically significant difference between the two groups (p = 0.52). When analyzed across age groups, no significant variation in the Widal positivity (p = 0.43) was observed. The group aged 21-40 years showed the highest positivity rate, accounting for 38.4% of all positive cases, followed by that aged 41-60 years (26.7%) and that aged below 20 years (23.3%). The least positivity was observed in the group aged above 60 years (11.6%).

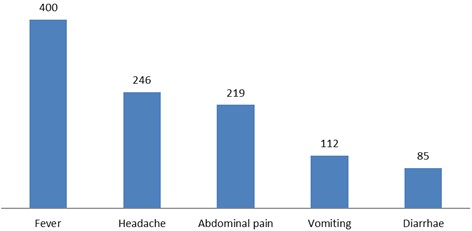

3. Clinical history (Fig. 1)

Fever was the most common presenting symptom and was observed in all 400 cases (100%). Headache was reported in 246 cases (61.5%), followed by abdominal pain in 219 cases (54.8%). Moreover, nausea and vomiting were recorded in 112 patients (28%), whereas constipation or diarrhea was observed in 85 patients (21.3%). Thus, while fever was uni- versal, gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and bowel disturbances were relatively less frequent.

4. Widal test results (Fig. 2)

Of the 400 cases tested, 314 (78.5%) were negative, while 86 (21.5%) were positive for the Widal test. Of the positive cases, an isolated elevation of O antigen titers (≥ 1:320) was the most frequent pattern, as observed in 58 cases (67.4%). A combined elevation of both the O and H antigens (≥ 1: 320) was observed in 11 cases (12.8%), while 1 case (1.2%) showed O:320 with H:160 and complete reactivity involving all antigens (O, H, AH, and BH ≥ 1:320). The remaining 15 cases (17.4%) showed lower titer patterns.

5. Antibody titer distribution (Table 3)

|

Antigen |

Titer (1:160) |

Titer (1:320) |

Titer (1:640) |

Negative |

Remarks |

|

O antigen |

14.0% |

81.4% |

4.6% |

– |

Most

frequent titer |

|

H antigen |

16.3% |

14.0% |

– |

69.8% |

Majority

negative for |

|

AH/BH antigen |

– |

1.2% each |

– |

– |

Low

positivity rate |

The O antigen titers were predominantly increased at 1:320 dilution, and isolated O antigen elevation was significantly more common than combined O and H elevation (p < 0.001). The mean H antigen titer among the positive cases was 1:142 ± 76 (p < 0.001), while the mean O antigen titer was 1:276 ± 89. A detailed titer breakdown showed that the O antigen titers were 1:320 in 70 cases (81.4%), 1:160 in 12 cases (14%), and 1:640 in 4 cases (4.7%). The H antigen titers were negative in 60 cases (69.8%), 1:160 in 14 cases (16.3%), and 1:320 in 12 cases (14%). Both the AH and BH antigen titers were negative in 85 cases (98.8%), with only 1 case (1.2%) showing titers of 1:320.

6. Demographic and clinical profile

In summary, of the 400 patients tested, 187 (46.75%) were male and 213 (53.25%) were female, with a median age of 28 years. The majority presented with symptoms of fever, headache, and abdominal discomfort, consistent with the typical typhoid fever symptoms.

This study shows a low Widal test positivity rate (21.5%) among clinically suspected typhoid fever cases, similar to the recent findings from other Indian studies16,17. The predom- inance of isolated O antigen elevation (67.4%) may reflect early infection, past exposure, or cross-reactivity with other Salmonella serovars and gram-negative organisms18,19.

The relatively small proportion of combined O and H antigen elevation (12.8%) suggests limited active infections, sup- porting earlier evidence that the Widal test performs poorly in endemic populations20,21. The lack of significant gender or age association is consistent with previous epidemiological reports22,23.

A key limitation is the absence of a control group of healthy individuals from the same community. In endemic regions, baseline antibody titers of ≥ 1:160 may occur in healthy individuals due to repeated subclinical exposures24. Thus, the true specificity of the Widal test cannot be determined from this study alone.

Seasonal variation was not evaluated, which may have influenced the test positivity, as typhoid incidence is known to increase during monsoon months. Thus, future studies should include temporal data to investigate such patterns.

The Widal positivity rate (21.5%) indicates a low diagnostic sensitivity in this clinical population. Since no culture confirm- ation was performed, the positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) were not presented, as their calculation without a reference standard could misrepresent the diagnostic accuracy.

Despite its simplicity and low cost, the Widal test continues to have limited clinical value as a stand-alone diagnostic tool. Newer rapid diagnostic tests such as Typhidot or Tubex TF have shown improved sensitivity and specificity25-27. Never- theless, in resource-limited areas, the Widal test remains useful when interpreted in conjunction with clinical findings and regional baseline titer data.

However, this study has several limitations that should be addressed when interpreting the results. First, the absence of blood culture confirmation compromised the ability to determine the diagnostic accuracy of the Widal test in terms of sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV. Second, a control group of healthy individuals was not included, which prevented the assessment of the baseline antibody titers within the local population. Third, the cross-sectional design of the study restricted the evaluation of the temporal changes and anti- body kinetics over the course of infection. Moreover, seasonal variations were not analyzed, which may have influenced the Widal positivity rate, as typhoid incidence often fluctuates with climatic changes, particularly during monsoon periods. Finally, information on previous typhoid vaccination was not obtained, and a previous immunization could have contributed to increased antibody titers in some participants.

In clinically suspected typhoid cases, the Widal test showed a low positivity rate (21.5%) with isolated O antigen elevation as the most common pattern. The findings of the present study emphasize the need for complementary diagnostic methods and locally standardized cutoff values to improve accuracy. Clinical correlation, regional antibody baseline data, and epidemiological context must always guide interpretation. Hence, future studies should also include blood culture con- firmation, healthy controls, and seasonal trend analysis to better evaluate the diagnostic value of serological testing in typhoid fever.

References

1. Crump JA, Luby SP, Mintz ED. The global burden of typhoid fever. Bull World Health Organ 2004;82:346-353

Google Scholar

2. Buckle GC, Walker CL, Black RE. Typhoid fever and para- typhoid fever: Systematic review to estimate global morbidity and mortality for 2010. J Glob Health 2012;2: 010401

Google Scholar

3. Ochiai RL, Acosta CJ, Danovaro-Holliday MC, Baiqing D, Bhattacharya SK, Agtini MD, et al. A study of typhoid fever in five Asian countries: disease burden and impli- cations for controls. Bull World Health Organ 2008;86: 260-268

Google Scholar

4. John TJ, Rajappan K, Arjunan KK. Communicable diseases monitored by disease surveillance in Kottayam district, Kerala state, India. Indian J Med Res 2004;120:86-93

Google Scholar

5. Shukla S, Patel B, Chitinis D. 100 years of Widal test & its reappraisal in an endemic area. Indian J Med Res 1997; 105:53-57

Google Scholar

6. Rasaily R, Dutta P, Saha MR, Mitra U, Bhattacharya SK, Manna B, et al. Value of a single Widal test in the diag- nosis of typhoid fever. Indian J Med Res 1993;97:104-107

Google Scholar

7. Lalremruata R, Chadha S, Bhalla P. Retrospective audit of the Widal test for diagnosis of typhoid fever in pediatric patients in an endemic region. J Clin Diagn Res 2014;8: DC22-DC25

Google Scholar

8. Bhutta ZA. Current concepts in the diagnosis and treat- ment of typhoid fever. BMJ 2006;333:78-82

Google Scholar

9. Keddy KH, Sooka A, Letsoalo ME, Hoyland G, Chaignat CL, Morrissey AB, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of typhoid fever rapid antibody tests for laboratory diagnosis at two sub-Saharan African sites. Bull World Health Organ 2011; 89:640-647

Google Scholar

10. Saha MR, Dutta P, Palit A, Dutta D, Bhattacharya MK, Mitra U, et al. A note on incidence of typhoid fever in diverse age groups in Kolkata, India. Jap J Infect Dis 2003; 56:121-122

Google Scholar

11. Dutta S, Sur D, Manna B, Sen B, Deb AK, Deen JL, et al. Evaluation of new-generation serologic tests for the diagnosis of typhoid fever: data from a community-based surveillance in Calcutta, India. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2006;56:359-365

Google Scholar

12. Olopoenia LA, King AL. Widal agglutination test - 100 years later: still plagued by controversy. Postgrad Med J 2000;76:80-84

Google Scholar

13. Prasad KJ, Oberoi A, Nanda A. Widal test: a reappraisal. J Postgrad Med 1999;45:70-73

14. Willke A, Ergonul O, Bayar B. Widal test in diagnosis of typhoid fever in Turkey. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 2002; 9:938-941

Google Scholar

15. House D, Wain J, Ho VA, Diep TS, Chinh NT, Bay PV, et al. Serology of typhoid fever in an area of endemicity and its relevance to diagnosis. J Clin Microbiol 2001; 39:1002-1007

Google Scholar

16. Gilman RH, Terminel M, Levine MM, Hernandez-Mendoza P, Hornick RB. Relative efficacy of blood, urine, rectal swab, bone-marrow, and rose-spot cultures for recovery of Salmonella typhi in typhoid fever. Lancet 1975;1:1211-1213

Google Scholar

17. Wain J, Hendriksen RS, Mikoleit ML, Keddy KH, Ochiai RL. Typhoid fever. Lancet 2015;385:1136-1145

18. Parry CM, Hien TT, Dougan G, White NJ, Farrar JJ. Typhoid fever. N Engl J Med 2002;347:1770-1782

19. mondiale de la Santé O, World Health Organization. Typhoid vaccines: WHO position paper - March 2018. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2018;93:153-172

20. Mogasale V, Maskery B, Ochiai RL, Lee JS, Mogasale VV, Ramani E, et al. Burden of typhoid fever in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic, literature-based update with risk-factor adjustment. Lancet Glob Health 2014;2:e570-580

Google Scholar

21. Maheshwari V, Kaore NM, Ramnani VK, Sarda S. A comparative evaluation of different diagnostic modalities in the diagnosis of typhoid fever using a composite reference standard: A tertiary hospital based study in Central India. J Clin Diagn Res 2016;10:DC01-DC04

Google Scholar

22. Narayanappa D, Sripathi R, Jagdishkumar JK, Rajani HS. Comparative study on the use of Widal test to stool culture in the laboratory diagnosis of typhoid fever. Int J Curr Microbiol App Sci 2015;4:613-621

Google Scholar

23. Bhutta ZA, Mansurali N. Rapid serologic diagnosis of pediatric typhoid fever in an endemic area: a prospective comparative evaluation of two dot-enzyme immuno- assays and the Widal test. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1999; 61:654-657

Google Scholar

24. Olsen SJ, Pruckler J, Bibb W, Nguyen TM, Tran MT, Nguyen TM, et al. Evaluation of rapid diagnostic tests for typhoid fever. J Clin Microbiol 2004;42:1885-1889

Google Scholar

25. Sherwal BL, Dhamija RK, Randhawa VS, Jais M, Kaintura A, Kumar M. A comparative study of Typhidot & Widal test in patients of typhoid fever. J Indian Med Assoc 2004;5:244-246

26. Kawano RL, Leano SA, Agdamag DM. Comparison of serological test kits for diagnosis of typhoid fever in the Philippines. J Clin Microbiol 2007;45:246-247

Google Scholar

27. Anagha K, Deepika B, Shahriar R, Sanjeev GK. Typhoid in pediatric age group in a rural tertiary care center: present scenario. Int J Curr Microbiol App Sci 2015;4:162-168

Google Scholar

Congratulatory MessageClick here!