pISSN : 3058-423X eISSN: 3058-4302

Open Access, Peer-reviewed

pISSN : 3058-423X eISSN: 3058-4302

Open Access, Peer-reviewed

Shankar Ganesh M,Venkateshwaramurthy Nallasamy

10.17966/JMI.2025.30.4.121 Epub 2026 January 01

Abstract

Fungal infections remain a global health issue, particularly for immunocompromised patients. Conventional antifungal agents, such as azoles, polyenes, and echinocandins, are often hampered by limited solubility, systemic toxicity, and inadequate tissue penetration, yielding suboptimal efficacy and fostering drug resistance. In response, drug delivery systems have emerged, offering revolutionary solutions to these issues. This review comprehensively discusses the new generation of advanced antifungal delivery systems, with an emphasis on nanotechnology-based platforms such as liposomes, polymeric nanoparticles, solid lipid nanoparticles, dendrimers, and smart hydrogels. Such platforms have superior efficacy in terms of targeting, controlled release, and reduced toxicity through pharmacokinetic improvement and enhanced biodistribution. Liposomal amphotericin B and SUBA-itraconazole have shown impressive clinical potential, whereas oral amphotericin B cochleates and nano-amphotericin B inhaled for lung infections are under clinical development. Other examples of next-generation localized delivery technologies include enzyme-sensitive hydrogels and nanocarrier-loaded dressings. Despite this promising translational potential, challenges such as manufacturing scalability, regulatory sophistication, and biological targeting specificity persist. However, interdisciplinary approaches drive advances in antifungal pharmacotherapy, particularly patient-friendly therapies. Integrating mycology and nanomedicine promises a paradigm shift in antifungal treatment, from systemic, toxic regimens to site-specific, durable, responsive therapies.

Keywords

Antifungal therapy Drug delivery systems Fungal infections Hydrogels Liposomes Nanocarriers

Fungal infections range from superficial skin conditions to life-threatening systemic diseases, affecting millions world- wide1-3. Major opportunistic fungi such as Candida, Crypto- coccus, Aspergillus, and dermatophytes cause high morbidity and mortality, especially in immunocompromised patients1,2. Traditional antifungal therapies (e.g., oral azole pills and intravenous polyenes such as amphotericin B [AmB]) have improved outcomes but often suffer from serious drawbacks: toxicity, poor solubility, limited tissue penetration, and emerg- ing drug resistance4. For example, AmB is a potent broad-spectrum fungicidal agent, but its conventional deoxycholate formulation is intravenous (IV)-only and highly nephrotoxic, with infusion-related side effects5-7. Likewise, azoles such as itraconazole and posaconazole have erratic oral absorption, and echinocandins require IV administration due to their poor oral bioavailability. These limitations can lead to suboptimal efficacy, frequent dosing, and systemic side effects4. To over- come these challenges, advanced drug delivery systems are being developed to enhance antifungal therapy. Recent years have seen a surge in nano-enabled delivery platforms, nanoparticles (NPs), liposomes, lipid carriers, hydrogels, and other novel formulations, designed to improve the targeting, efficacy, and safety of antifungal drugs8. This review provides a comprehensive overview of these cutting-edge antifungal delivery technologies, comparing them with conventional systems and highlighting their applications across diverse fungal infections. Key clinical advances, ongoing trials, and the challenges and future prospects of these novel delivery approaches are discussed in a formal academic perspective.

1. Conventional formulations

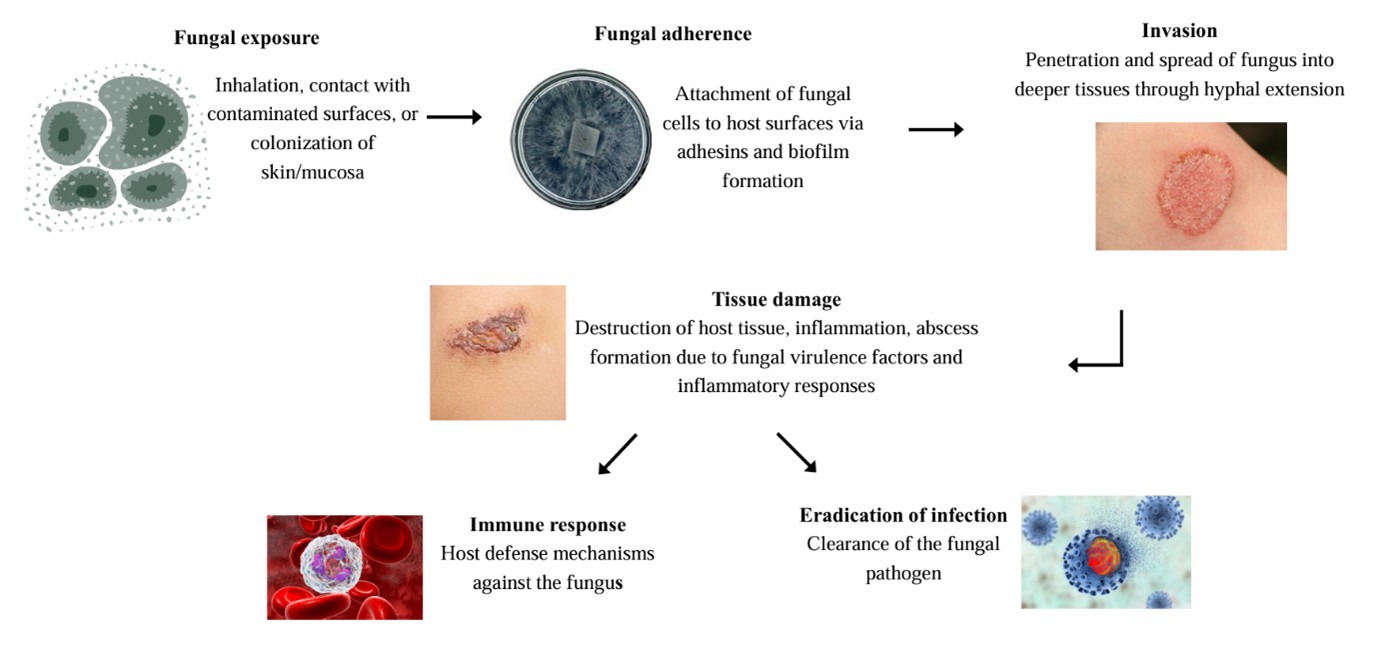

The current standard antifungal drugs are classified as follows: polyenes (e.g., AmB), azoles (e.g., fluconazole, itra- conazole, and voriconazole), echinocandins (e.g., caspofungin), and others (allylamines and pyrimidines). These are typically delivered as oral tablets, capsules, or intravenous infusions and, in some cases, as topical creams or suspensions for localized infections. For instance, oral fluconazole is a first-line therapy for candidiasis, voriconazole IV/oral for invasive aspergillosis, and AmB IV for severe systemic infections9-11. Topical azole creams (clotrimazole and miconazole) or terbinafine are used for dermatophyte skin infections and Candida vaginitis, whereas ocular fungal infections and cryptococcal meningitis often necessitate IV treatment (and sometimes intrathecal therapy) due to poor drug penetration of ocular and CNS barriers12. Fig. 1 illustrates the pathogenesis of fungal infection.

2. Limitations

Despite their efficacy, traditional delivery forms have not- able drawbacks. Many antifungals are hydrophobic or poorly water-soluble, resulting in low bioavailability and erratic ab- sorption4. Itraconazole, for example, has variable oral absorp- tion and requires cyclodextrin solutions for IV use, whereas AmB is virtually insoluble in water13-15. Limited penetration of drugs into certain tissues (e.g., blood–brain barrier in crypto- coccal meningitis, nail bed in onychomycosis and biofilm-embedded pathogens) can result in subtherapeutic concen- trations at the infection site. Moreover, conventional systemic therapy often causes off-target toxicity because antifungal agents can damage human cells (fungi are eukaryotes that share some pathways with host cells). AmB deoxycholate is notorious for nephrotoxicity and infusion reactions (fever, chills, and hypotension), requiring hospitalization and moni- toring16-18. Azoles induce systemic side effects (hepatotoxicity and QT prolongation) and drug–drug interactions due to CYP450 inhibition. Echinocandins must be given IV, limiting outpatient use. Furthermore, long treatment courses needed for deep-seated or chronic infections (e.g., ≥12 weeks for fungal osteomyelitis or onychomycosis) increase the risk of adverse effects and patient noncompliance19. Recurrent or refractory infections (such as chronic Candida vaginitis or invasive aspergillosis in immunosuppressed patients) pose additional challenges as escalating doses of conventional drugs can worsen toxicity while drug resistance persists20. These issues underscore the need for improved delivery systems that can enhance drug solubility, target drugs to infection sites, and reduce systemic exposure.

3. Rationale for advanced delivery

Modern drug delivery research aims to address the above limitations by reformulating antifungals into carriers that modulate pharmacokinetics and biodistribution. By incorporating antifungal agents into specialized delivery systems, scientists hope to improve tissue targeting and penetration, maintain therapeutic drug levels longer, and minimize ex- posure to healthy tissues21. Important motivations include overcoming poor aqueous solubility, enhancing uptake into infected cells or biofilms, circumventing efflux pumps that cause resistance, and enabling new administration routes (e.g., inhalation or transdermal delivery of drugs that currently can only be given IV)4,21. In summary, while traditional oral and IV antifungal therapies remain the treatment backbone, their shortcomings have catalyzed the development of novel delivery platforms to achieve more effective and safer antifungal therapies.

|

Formulation |

Indication/Target |

Status |

Key

Outcomes/Benefits |

|

Liposomal Amphotericin |

Invasive fungal infections |

Approved |

Equally effective as

conventional AmB for systemic mycoses with markedly reduced nephrotoxicity

and infusion reactions. |

|

SUBA® Itraconazole

(Tolsura®) ‐ amorphous |

Broad use in endemic |

Approved |

Itraconazole formulated

as microencapsulated amorphous NPs for oral delivery, leading to ~2-3× higher bioavailability. Achieves

therapeutic levels with lower doses, |

|

Oral Amphotericin B |

Cryptococcal

meningitis, invasive candidiasis, etc. (patients intolerant or refractory to

standard |

Phase II trials;

compassionateuse |

Oral capsule form of

AmB (phospholipid-calcium

cochleate) enabling gastrointestinal |

|

Nebulized AmB‐PMA |

Prophylaxis of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis |

Preclinical |

An inhaled amphotericin

B‐polymethacrylate NP (~20 nm) for lung delivery showed >99% fungal kill in mouse lungs and prevented

aspergillosis development33. Protected mice from deadly Aspergillus

pneumonia, with a 90% reduction in lung inflammation. The aerosol was

nontoxic to lung tissue. Proof- |

|

Topical Liposomal |

Cutaneous dermatophyte |

Preclinical / |

Liposome-encapsulated

azoles (e.g. liposomal fluconazole, ketoconazole, and terbinafine) in gels

have shown enhanced skin penetration and localized drug retention. In ex vivo skin models and small trials,

these formulations achieved higher antifungal concentrations in the epidermis

and nail beds compared to conventional creams34. Expected to reduce |

Nanotechnology has revolutionized drug delivery in recent years, offering versatile platforms for carrying and releasing therapeutic agents. Numerous nanocarriers have been ex- plored for antifungal drug delivery, including polymeric and lipid NPs, liposomes, nanoemulsions, solid lipid NPs, nanogels, micelles, dendrimers, and inorganic nanomaterials22-28. These nanomedicine approaches allow drugs to be encapsulated or attached to sub-micrometer carriers (typically 10-300 nm), which can alter the drug's pharmacokinetic profile and im- prove its therapeutic index22,23.

Table 1 provides representative examples of how nano- formulations are being applied to different antifungal drugs and indications. In general, nanoparticulate delivery offers several key advantages over conventional formulations:

Improved Solubility and Stability: Drugs encapsulated in NPs can be dispersed in aqueous media even if the free drug is hydrophobic. The nanocarrier matrix protects unstable drugs from degradation. For example, nano- liposomes and polymeric NPs increase the solubility of poorly water-soluble azoles, improving their bioavail- ability22,23.

Controlled and Sustained Release: Nanocarriers can be engineered to release the drug slowly over time or in response to specific stimuli, maintaining therapeutic levels longer and reducing the dosing frequency. This is especially useful for chronic fungal infections, requiring prolonged therapy.

Targeted Delivery: Owing to their small size and surface modifiability, NPs can penetrate biological barriers and be functionalized with targeting ligands (e.g., antibodies, peptides, or sugars) that recognize fungal cells or infected tissue35-37. This active targeting can concentrate the drug at the site of infection while sparing healthy tissues, thereby enhancing efficacy and reducing systemic toxicity. For instance, NPs decorated with specific ligands could, in principle, bind to components of fungal cell walls or to receptors on host phagocytes that are home to infection sites.

Enhanced Cellular Uptake: Nano-sized carriers are readily absorbed by phagocytic immune cells (such as macro- phages), which often aggregate at sites of fungal infection. Drug-loaded NPs can thus act as "Trojan horses," delivering antifungals intracellularly to organisms such as Histoplasma or Cryptococcus that may reside in macrophages38. This mechanism may also facilitate the crossing of difficult barriers (NPs can be ferried across the blood–brain barrier inside migrating phagocytes, improving drug delivery to the central nervous system (CNS).

Reduced Toxicity and Improved Tolerability: By controlling drug release and distribution, nano-delivery can prevent the high peak plasma concentrations that cause many side effects of traditional formulations. For example, studies have shown that encapsulating AmB in nanoscale carriers can maintain antifungal efficacy with remarkably less toxicity than a free drug39,40. Dosing requirements may also be lowered; certain nanoformulations exhibit greater antifungal potency per unit of drug than the free form, possibly due to improved pharmacodynamics or synergistic effects.

Notably, NP-based delivery systems have demonstrated success across a spectrum of fungal pathogens. Researchers have developed and tested nanoformulations for major yeast and mold infections, aiming to improve the treatment of candidiasis, aspergillosis, cryptococcosis, and dermatophytoses, among others. Below, we discuss key categories of advanced delivery platforms, with an emphasis on NPs, liposomes, and hydrogels, and their applications to different fungal diseases.

Lipid-based and liposomal nanocarriers, such as PEGylated systems, may induce CARPA and other immune reactions by several mechanisms involving natural IgM-/IgG-binding activating the classical pathway, mannose-covered or anionic surfaces activating the lectin pathway, and direct alternative pathway "tick-over," with C3b/iC3b opsonization promoting reticuloendothelial clearance. Clinically, CARPA occurs within minutes of administration as flushing, chest discomfort, dyspnea, hypotension, or even pulmonary hypertension, and PEGylated liposomal doxorubicin and liposomal AmB are well-documented cases41. The repeated dosing may stimulate or augment anti-PEG antibodies, precipitating the accelerated blood clearance phenomenon that markedly lowers systemic exposure and can follow cross-exposure to other PEGylated drugs. Formulation parameters like PEG density, surface charge, targeting ligands, and protein corona composition remarkably affect immunogenicity risk, whereas infusion rate affects acute CARPA severity. Evaluation tactics involve in vitro human serum CH50/AH50 assays, quantification of C3a/C5a/sC5b-9, ex vivo whole-blood experiments, and in vivo porcine models that mimic cardiopulmonary alterations41. Risk-mitigation strategies include gradual or slow infusions, premedication, and stealth design chemistries that reduce complement recruitment and for background anti-PEG prevalence.

1. Liposomal AmB

The flagship example of liposomal delivery in antifungal therapy is liposomal AmB. AmBisome® (liposomal AmB) was the first nano-formulation of AmB, developed in 1990 to replace the conventional AmB deoxycholate formulation42. In this formulation, AmB is entrapped within small unilamellar liposomes. Clinically, liposomal AmB has demonstrated efficacy equivalent to that of conventional AmB against various systemic mycoses (invasive candidiasis, cryptococcal meningitis, aspergillosis, mucormycosis, etc.), while dramatically reducing the drug's toxicity. The lipid vesicles act as a sink that absorbs AmB molecules, lessening their interaction with mammalian cell membranes; as a result, liposomal AmB causes far less renal damage and infusion reactions compared to free AmB43. Patients can tolerate higher cumulative doses, improving the treatment of refractory infections. Several liposomal AmB products are now marketed globally (e.g., AmBisome®, FungisomeTM, and AnfogenTM), and they have become the standard of care for many invasive fungal infections44. For instance, liposomal AmB is preferred over conventional AmB for initial therapy of cryptococcal meningitis in HIV and for visceral leishmaniasis (a parasitic disease) due to its superior safety profile. It exemplifies how nano-delivery can increase the therapeutic index, preserving AmB's life-saving efficacy while enabling more targeted, less toxic delivery.

2. Lipid NPs and emulsions

Beyond true liposomes, other lipid-based nanocarriers have been widely explored for antifungals. Solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs) are sub-200 nm particles made of solid lipids (fatty acids, triglycerides, etc.) that remain solid at body temperature and are often stabilized by surfactants. Nanostructured lipid carriers (NLCs) are similar but include a mix of solid and liquid lipids to form a less-ordered matrix. These systems can incorporate hydrophobic antifungal drugs in their lipid core, improving solubility and providing controlled release. They are especially promising for topical and transdermal delivery because the lipid matrix can enhance penetration into the stratum corneum and act as a depot within the skin layers19. For example, clotrimazole-loaded SLNs have been developed for vulvovaginal candidiasis. In an in vivo model of vaginal infection, a clotrimazole SLN formulation achieved better therapeutic outcomes than conventional clotrimazole cream45. Similarly, econazole, an imidazole antifungal, was formulated into an SLN gel to overcome its poor water solubility. The SLN markedly improved econazole penetration through pig skin compared to a traditional gel, leading to more effective delivery to the infection site. Miconazole, another common topical azole, has also benefited from SLN technology: in vitro and animal studies showed that mico- nazole nitrate SLNs increased drug accumulation in skin and enhanced antifungal activity against Candida in a rat model of cutaneous candidiasis46. An SLN-based hydrogel of mico- nazole eradicated fungal lesions more effectively than a free miconazole gel. These findings suggest that lipid NPs can improve the treatment of dermatophytic and cutaneous candidiasis by ensuring the drug permeates into infected epidermal layers and hair/nail units, while limiting systemic absorption (and thus side effects).

Lipid NPs are also being explored for the ocular and pulmonary delivery of antifungals. Ocular fungal infections like keratitis are hard to treat with eye drops because of poor corneal penetration and tear washout. An itraconazole-loaded SLN suspension for ocular use was shown to increase drug retention time on the cornea and demonstrated efficacy against Aspergillus flavus in an experimental keratitis study47. For pulmonary aspergillosis, NLCs and liposomes have been formulated as inhalable aerosols or dry powders. As one example, itraconazole-loaded nanostructured lipid carriers for inhalation have been studied, aiming to deliver the drug directly to the lungs to treat or prevent invasive Aspergillus infection48. These inhalable formulations could achieve high local drug levels in the respiratory tract while minimizing systemic exposure, an approach particularly relevant for prophylaxis in neutropenic patients at risk for invasive pul- monary aspergillosis.

3. Niosomes, emulsions, and others

A variety of other lipid-based nano-delivery systems have shown promising potential. Niosomes are non-ionic sur- factant vesicles (structurally analogous to liposomes but made of synthetic surfactants and cholesterol) that can en- capsulate antifungals; niosomal gels of drugs like miconazole have exhibited improved transdermal delivery in studies48. Nanoemulsions, colloidal droplets of oil in water that have been used to solubilize azoles for topical or oral administration, with studies indicating faster skin absorption and efficacy against dermatophytes. Transfersomes (ultradeformable lipo- somes) and ethosomes (ethanol-containing vesicles) are specialized vesicles designed to penetrate intact skin barriers; econazole and ketoconazole formulated in transfersome gels or ethosomal gels achieved deeper skin delivery than conventional formulations in experimental settings49. These lipid-based nanocarriers collectively expand the options for delivering antifungals via non-oral routes, including trans- dermal patches, inhalers, ocular inserts, and vaginal gels, thereby opening new avenues to treat infections that are localized or where systemic therapy is problematic.

Polymeric NPs are another major class of drug delivery systems, typically composed of biocompatible polymers that entrap or conjugate the drug. Common materials include poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA), polylactic acid (PLA), chitosan, and other biodegradable polymers. These NPs (often 50-200 nm) can provide sustained release of antifungals as the polymer matrix slowly degrades, and they can be engineered with functional surfaces for targeted delivery or improved mucoadhesion. Polymeric NPs have shown con- siderable potential to reduce the toxicity and enhance the efficacy of antifungal drugs. For instance, encapsulating AmB in PLGA NPs was found to maintain antifungal activity while reducing damage to human cells due to more controlled drug release50. In one study, AmB-loaded PLGA-PEG NPs exhibited a lower minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) against Candida albicans compared to free AmB (Fungizone®), in- dicating enhanced potency. In vivo, these AmB NPs protected mice from systemic candidiasis with reduced nephrotoxicity relative to conventional AmB (as reported in preclinical evalu- ations). Functionalization of polymeric NPs with targeting ligands can further improve outcomes: a recent example is galactosamine-modified PLGA NPs delivering AmB. Galacto- samine on the NP surface helps target Candida since Candida cells and macrophages have lectin receptors that bind galac- tose. The AmB-loaded PLGA-PEG-galactosamine NPs showed higher antifungal efficacy in vitro than non-targeted NPs or free drugs. This illustrates how polymeric carriers can be tailored for specific pathogen targeting (often by exploiting pathogen-specific surface carbohydrates or host-cell tropisms).

Dendrimers are another polymer-based platform of interest. They are highly branched, tree-like macromolecules that can host drugs either in their interior voids or attached to surface groups. Their well-defined nanometer size and multivalent surface make them attractive as delivery vehicles51. In anti- fungal delivery, dendrimers (such as polyamidoamine dend- rimers) have been studied for their potential as carriers for azoles and amphiphilic drugs. A dendrimer-based formulation of ketoconazole, for example, demonstrated improved water solubility and was formulated as a topical hydrogel that enhanced drug penetration for local therapy. Dendrimers can also disrupt fungal cell membranes on their own if de- signed with cationic or amphiphilic surface groups, providing a synergistic antifungal effect in some cases52. However, is ensuring biocompatibility is challenging, high-generation dendrimers with many charged surface groups can be hemo- lytic or cytotoxic. Ongoing research focuses on PEGylated or otherwise modified dendrimers that retain efficacy but are safer for systemic use.

Another interesting polymeric system is polymeric micelles, nano-sized (10-100 nm) aggregates of amphiphilic copoly- mers that self-assemble in water. These have a hydrophobic core that can solubilize lipophilic drugs and a hydrophilic shell (often PEG) that stabilizes particles in biological fluids. Polymeric micelles loaded with itraconazole, voriconazole, and other azoles have been investigated to improve solubility and distribution. Micellar itraconazole formulations have shown the ability to deliver drugs orally or intravenously without the need for cyclodextrin (which is used in the current IV formulation and can cause nephrotoxicity). Some micelle formulations are in early clinical development for invasive fungal infections. Polymeric nanocapsules (a subtype of NPs with a core-shell structure) have also been applied for drugs like fluconazole, allowing sustained release in oral and topical applications53.

Overall, polymeric nanocarriers offer a highly tunable plat- form. By adjusting polymer composition, molecular weight, and surface chemistry, researchers can design antifungal NPs with the desired release profiles and targeting capabilities. Many polymer-based formulations are still in preclinical stages, but they hold promise for delivering drugs to difficult sites (like the brain, eyes, or inside phagocytes) and for creating long-acting depot antifungals that could, for example, treat onychomycosis or cryptococcal meningitis with far fewer doses than today's therapies.

Beyond organic carriers, inorganic NPs (such as metals and metal oxides) have been explored due to their intrinsic antimicrobial properties and unique functionalities. Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) are the most widely studied inorganic agents; silver has natural antifungal and antibacterial activity by generating reactive oxygen species (ROS) and disrupting microbial membranes. Nanosilver can, thus, serve a dual role: acting as an antifungal itself and as a carrier for additional drugs. Studies have shown that conjugating AmB to biogenic silver NPs markedly enhanced the drug's antifungal efficacy against Candida species compared to AmB alone54. The combination leveraged the membrane-perturbing effects of AgNPs with the fungicidal action of AmB. Similarly, AgNPs have been combined with fluconazole or with polyenes like nystatin to overcome resistant strains—the NPs appear to increase the local concentration of the drug at the fungal cell surface and may help in penetrating biofilms55. Another novel approach is using silver nanowires (high-aspect ratio nanostructures) as drug shuttles: one study created a com- posite where silver nanowires were loaded with zinc ferrite (ZnFe2O4) magnetic NPs and showed that these could pene- trate Candida albicans biofilms and release ZnFe2O4 inside, resulting in fungal cell damage via generated ROS52. This kind of nano-hybrid system (combining metallic and polymeric components) represents an emerging strategy to tackle tough biofilm-associated infections on medical devices or surfaces.

Iron oxide NPs (magnetic NPs) have been studied for ther- anostic uses, for example, delivering antifungals while also serving as magnetic resonance imaging–visible tracers to localize infection. Gold NPs have been conjugated with anti- fungal peptides and evaluated for topical use, leveraging gold's ease of surface functionalization. However, for systemic use, inorganic NPs face concerns about long-term safety, biodegradability, and accumulation in organs. Therefore, many current applications of inorganic nanomaterials in mycology are geared toward topical therapies, coatings for catheters and implants (to prevent fungal biofilm formation), or combin- ation therapies where they act as adjuvants to conventional drugs.

Increasingly, researchers have combined organic and in- organic elements to create hybrid nanocarriers. For instance, chitosan-coated AgNPs or magnetic NPs encapsulated in polymeric shells can yield bioactive and biocompatible systems. Some "smart" nanosystems are being designed to respond to the fungal infection microenvironment, for example, particles that release their drug payload in response to acidic pH, high enzymatic activity, or other conditions typical of infection sites. These advanced designs remain largely experimental but ex- emplify the next generation of antifungal delivery strategies56.

Hydrogels are three-dimensional networks of hydrophilic polymers capable of holding large amounts of water, making them excellent vehicles for localized and sustained drug delivery. In antifungal therapy, hydrogels have gained atten- tion for topical and implantable depots, as well as for novel responsive delivery platforms. They can be formulated as creams, injectable solutions that gel in situ, wound dressings, or inserts for ocular and vaginal infections. Hydrogels provide a reservoir from which antifungal drugs can diffuse slowly, maintaining a high local concentration over extended periods while limiting systemic uptake57.

1. Topical and local hydrogels

One important application is in the treatment of cutaneous and subcutaneous fungal infections (dermatophyte skin infections, onychomycosis, and fungal wound infections). Traditional treatment of nail fungus or ringworm often requires long systemic therapy or daily topical application for months. Hydrogels can improve drug residence times at these sites. For example, researchers have developed an injectable in situ–crosslinking hydrogel loaded with AmB for local therapy of refractory fungal infections (such as fungal abscesses or osteomyelitis). In a preclinical study, this hydrogel (formed by mixing a dextran-aldehyde AmB conjugate with crosslinkers) provided continuous release of AmB for 11 days in vitro and maintained fungicidal activity against Candida albicans for over 3 weeks58. When injected into a mouse model, it achieved high local drug levels without marked tissue toxicity or systemic exposure. This approach of local depot injection could be valuable for treating fungal infections in bones or prosthetic joints, where systemic drugs have poor penetration, and surgery might be the only alternative.

For superficial infections, hydrogel formulations of azoles and polyenes have shown improved performance over con- ventional creams. A recent study reported a nystatin nano- capsular hydrogel for cutaneous candidiasis that led to superior antifungal outcomes in a murine model, indicating better drug delivery into the skin. Chitosan-based hydrogels containing econazole or miconazole have also been tested for dermato- phytoses, leveraging chitosan's innate antifungal and film-forming properties to enhance efficacy. These hydrogels often demonstrate stronger adhesiveness to skin or nail surfaces (bioadhesion), prolonging the contact time of the drug. In the case of onychomycosis (fungal nail infection), a common approach is to use keratinolytic agents (like urea) in a hydrogel alongside the antifungal to soften the nail and then allow sustained drug release to penetrate the nail bed. Such com- bination hydrogel therapies have shown faster clearing of nail fungus in pilot studies, addressing a remarkable unmet need in dermatology34.

2. Stimuli-responsive "Smart" hydrogels

The frontier of hydrogel research involves materials that respond to fungal infection triggers to release drugs on-demand. A remarkable recent advance is the development of enzyme-responsive hydrogels for antifungal delivery. Fungal pathogens like Candida albicans secrete tissue-degrading enzymes (e.g., aspartyl proteases) that facilitate invasion. Researchers have harnessed this trait: Vera-González et al. (2024) designed a hydrogel that remains intact until it en- counters Candida proteases, which then cleave peptide linkers in the gel and cause it to disintegrate, releasing its payload59. In this case, the payload was a liposome-encapsulated anti- fungal drug embedded in the hydrogel matrix. The fungi-triggered hydrogel showed no release in normal tissue fluid but degraded and released the drug in the presence of C. albicans proteases. In lab tests, this smart hydrogel completely eradicated C. albicans cultures while remaining stable and nontoxic in sterile wound fluid. Such a system could be applied as a local implant or wound coating that "senses" an infection—if fungal growth occurs, the drug is automatically dispensed at the site, potentially stopping the infection in its early stages. This on-demand approach also helps limit un- necessary drug exposure, which is beneficial for antimicrobial stewardship (only infected areas get high drug concentrations, reducing the chance of side effects or resistance elsewhere).

Hydrogels can also serve as combination platforms. The above example combined liposomal nanocarriers within a hydrogel, mixing the benefits of nano-encapsulation and controlled release. Other combinations include nanofiber-hydrogel composites for wound dressing: electrospun nano- fibers loaded with antifungals can be embedded in a hydrogel sheet that is applied to an infected burn or ulcer, continuously delivering drugs and also absorbing exudates. These anti- fungal wound dressings are in the experimental stages but have shown activity against Candida and Aspergillus in infected wound models60.

In summary, hydrogel-based delivery is particularly prom- ising for site-specific antifungal therapy, whether it be a topical gel for skin infection, an intracavitary gel for sinus fungal balls, or an injectable depot for an infected tissue space. Hydrogels can dramatically improve local drug concen- trations and treatment duration by addressing scenarios where systemic therapy is inadequate or risky.

Advanced antifungal delivery systems have progressed from the lab to the clinic at an accelerating pace. Several nano-formulated drugs are already in clinical use or late-stage trials, demonstrating real-world benefits.

1. Liposomal AmB is a prime success story

It transformed AmB from a highly toxic IV drug into a safer therapy, validated by clinical trials and decades of use. Another approved advance is SUBA-itraconazole (an example of using nanoscale engineering to create amorphous drug particles that dissolve more readily), which addresses the erratic absorption of itraconazole and has been adopted in clinical practice61. The oral AmB cochleate (MAT2203) is currently in Phase II and has generated excitement by showing that even a notoriously IV-only drug can be made orally available with use of nanotechnology62. Early patient outcomes suggest it can offer a much-needed option for long-term oral AmB therapy (for instance, for cryptococcal meningitis maintenance therapy, or treating invasive fungal infections in outpatient settings)62.

Inhaled antifungal delivery is another area moving toward clinical reality. Beyond the NP prophylaxis in Table 1, hospitals have already experimented with aerosolized liposomal AmB for prophylaxis in high-risk patients. Studies report that inhaled liposomal AmB given to leukemia and transplant patients markedly reduced the incidence of invasive aspergillosis, without severe pulmonary toxicity63. This has led to inhaled AmB being used as an adjunct prophylaxis in some centers (e.g., 12.5 mg inhaled Ambisome twice weekly in neutropenic patients). Nano-delivery could further improve this approach by ensuring uniform lung deposition and drug stability.

For topical fungal infections, some nano-formulations are close to market. For example, a nanoemulsion formulation of ciclopirox for onychomycosis and a liposomal luliconazole gel for an athlete's foot are in late-stage development, aiming to shorten the treatment duration. Liposomal AmB gels have been applied in clinical trials for cutaneous leishmaniasis and could be repurposed for cutaneous fungal infections. In ophthalmology, a hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin NP eye drop of natamycin (to treat fungal keratitis) has entered clinical testing, seeking to improve drug penetration into the cornea compared to the standard natamycin suspension.

Notably, while many advanced formulations show tre- mendous promise, only a few have so far gained regulatory approval. Most remain in the investigational or early clinical trial stages. The translation from positive laboratory results to human use can be slow as it requires a demonstration of safety, scalability, and clear superiority or added value. None- theless, the clinical pipeline is rich. As of 2025, multiple clinical trials are underway evaluating nano-carriers: e.g., a Phase II trial of a nanostructured itraconazole inhalation powder for allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, a Phase I trial of dendrimer-based fluconazole gel for recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis, and compassionate use of AgNP creams in some refractory chromoblastomycosis cases64. Official clinical trial databases and regulatory documents increasingly mention nanoformulations in the antifungal context, underlining that the field is on the cusp of broader clinical adoption.

Advanced antifungal delivery systems offer clear bene- fits, but their development and implementation face note- worthy challenges. One major issue is formulation stability and manufacturability. Many nanocarriers (liposomes and nanoemulsions) can be sensitive to storage conditions, prone to aggregation or drug leakage over time. Ensuring a long shelf-life and consistent quality for commercial products can be difficult and may increase production costs. Liposomal formulations, for instance, are more expensive to produce than simple oral pills, which have limited their widespread use despite clinical advantages65. The high production cost and complexity (requiring sterile, specialized facilities) mean that advanced formulations might be inaccessible in resource-limited settings where fungal infections are often the deadliest. Future efforts in process engineering and scalable manufac- turing (such as spray-drying techniques for nanoformulations) will be crucial to making these therapies broadly available.

1. Pharmacokinetic and regulatory hurdles

Novel delivery systems can exhibit different pharmaco- kinetics that complicate dosing and regulatory approval. The body's reticuloendothelial system (RES) may clear NPs rapidly or sequester them in organs like the liver and spleen, affecting the drug distribution. Ensuring that the carrier itself is nontoxic and biodegradable is paramount, any carrier that persists (as inorganic particles might) raises safety questions for chronic use. Regulatory agencies require extensive toxicology evalu- ation of not just the drug but also the carrier materials and degradation products. For example, with polymeric NPs, the metabolites of the polymer must be shown to be safe. Gaining approval for combination products (e.g., a drug + device like a catheter coated in antifungal nanomaterials, or a drug + two-component system like liposome-in-hydrogel) can also be complex as it may fall under multiple regulatory categories.

2. Targeting complexity

While the concept of targeting fungal infections is attractive, achieving it is nontrivial. Unlike cancer cells or bacteria, fungi are eukaryotic cells that share many surface features with human cells, making it hard to find unique targets. Some targeting strategies under exploration include mannosylated NPs that home in on macrophage mannose receptors (lever- aging the fact that many pathogenic fungi like Candida and Histoplasma interact with mannose receptors) and antibodies against fungal cell wall components (such as β-glucans) attached to liposomes. These approaches are still in experi- mental phases; they add complexity and cost, and there is a risk of off-target immune interactions. Furthermore, the dense polysaccharide cell wall of fungi can itself be a barrier, NPs must sometimes penetrate the fungal cell wall to effectively deliver a drug into the fungal cell (e.g., delivering an siRNA or intracellular-acting drug). Innovative solutions like cell-penetrating peptide functionalization or exploiting "Trojan horse" uptake via phagocytes are being investigated to address this66.

3. Potential resistance and interactions

There is a theoretical concern that suboptimal release from a depot or NP could expose fungi to low drug concentrations for prolonged periods, which might promote drug resistance. For example, if a poorly designed slow-release system leaches tiny amounts of drugs, the pathogen could adapt. Careful design is needed to ensure therapeutic levels at all times. Additionally, combining new delivery systems with existing antifungals requires pharmacodynamic interactions. Some nanoformulations may have inherent antifungal action (e.g., silver), which could either synergize or antagonize the drug's effect. As these systems enter clinical trials, monitoring for any unexpected toxicities or efficacy issues is essential.

Looking ahead, the future of antifungal therapy will likely feature multifunctional delivery systems and novel routes of administration. On the horizon are "theranostic" nano- medicines that can diagnose and treat fungal infections simultaneously, for example, magnetic NPs that target fungal lesions and allow MRI imaging of the infection burden while carrying an antifungal payload. Researchers are also exploring immuno-nanomedicine approaches: NPs delivering immuno- modulators or cytokines alongside antifungals to boost the host's antifungal immune response. Another promising area is gene and RNA interference therapy for fungal infections, nanoscale carriers might someday deliver siRNA or antisense oligonucleotides to knock down essential fungal genes or virulence factors in situ. While such molecular therapies are still distant, the delivery vehicles being developed now lay the groundwork for their future implementation67.

In terms of practical treatment modalities, we can expect more targeted local therapies to complement systemic drugs. For instance, long-acting antifungal implants could be placed during surgery to prevent relapse of fungal osteomyelitis; inhaled prophylactic nanodrugs might become routine in leukemia wards during high-risk periods; and intravaginal antifungal rings (analogous to contraceptive rings) could provide month-long protection against recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis using NP depots68. These approaches would mark- edly change the management of fungal diseases, emphasizing prevention and localized treatment to reduce reliance on lengthy systemic therapy.

Despite these challenges, the trajectory of research and the early successes in clinical translation are optimistic. NPs, liposomes, and hydrogels have firmly established their poten- tial to enhance antifungal drug delivery. Continued interdis- ciplinary collaboration, among mycologists, pharmacologists, materials scientists, and clinicians is driving innovation in this field. As new delivery systems continue to address the shortcomings of conventional therapy, the vision of more effective, less toxic, and more patient-friendly antifungal treat- ments is gradually being realized.

Advances in nanocarriers, liposomes, and hydrogels are transforming antifungal therapy by enhancing drug solubility, site-specific drug delivery, and safety profiles. Clinically proven products like liposomal AmB and SUBA-itraconazole and pro- mising products like oral AmB cochleates and lipid inhalation formulations demonstrate the evolution of systemic, toxic regimens to patient-friendly, localized treatments. Although production, regulatory, and targeting problems still exist, ongoing interdisciplinary research and strict clinical testing are likely to increase the role of these delivery systems, providing better and less toxic treatments for common and refractory fungal infections.

References

1. Rai M, Ingle AP, Pandit R, Paralikar P, Gupta I, Anasane N, et al. Nanotechnology for the treatment of fungal infections on human skin. In: The microbiology of skin, soft tissue, bone and joint infections. Cambridge (MA): Academic Press; 2017:169-184

Google Scholar

2. Pianalto KM, Alspaugh JA. New horizons in antifungal therapy. J Fungi 2016;2:26

Google Scholar

3. Brown GD, Denning DW, Gow NAR, Levitz SM, Netea MG, White TC. Hidden killers: human fungal infections. Sci Transl Med 2012;4:165rv13

Google Scholar

4. Nami S, Aghebati-Maleki A, Aghebati-Maleki L. Current applications and prospects of nanoparticles for antifungal drug delivery. EXCLI J 2021;20:562-584

Google Scholar

5. Hamill RJ. Amphotericin B formulations: a comparative review of efficacy and toxicity. Drugs 2013;73:919-934

Google Scholar

6. National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem Compound Summary for Amphotericin B (CID: 1972). Accessed 2020 Apr 22. Available from: https:// pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/amphotericin-b

Google Scholar

7. Akinosoglou K, Rigopoulos EA, Papageorgiou D, Schinas G, Polyzou E, Dimopoulou E, et al. Amphotericin B in the era of new antifungals: Where will it stand? J Fungi (Basel) 2024;10:278

Google Scholar

8. Sousa F, Ferreira D, Reis S, Costa P. Current insights on antifungal therapy: novel nanotechnology approaches for drug delivery systems and new drugs from natural sources. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2020;13:248

Google Scholar

9. Perfect JR, Dismukes WE, Dromer F, Goldman DL, Graybill JR, Hamill RJ, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of candidiasis: 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2010;50: 291-322

Google Scholar

10. Patterson TF, Thompson GR 3rd, Denning DW, Fishman JA, Hadley S, Herbrecht R, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of aspergillosis: 2016 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2016;63:e1-e60

Google Scholar

11. Hussien A, Lin CT. CT findings of fungal pneumonia with emphasis on aspergillosis. Emerg Radiol 2018;25:685-689

Google Scholar

12. Sahni K, Singh S, Dogra S. Newer topical treatments in skin and nail dermatophyte infections. Indian Dermatol Online J 2018;9:149-158

Google Scholar

13. Buchanan CM, Buchanan NL, Edgar KJ, Klein S, Little JL, Ramsey MG, et al. Pharmacokinetics of itraconazole after intravenous and oral dosing of itraconazole-cyclodextrin formulations. J Pharm Sci 2007;96:3100-3116

Google Scholar

14. Faustino C, Pinheiro L. Lipid systems for the delivery of amphotericin B in antifungal therapy. Pharmaceutics 2020;12:29

Google Scholar

15. Willems L, van der Geest R, de Beule K. Itraconazole oral solution and intravenous formulations: a review of pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. J Clin Pharm Ther 2001;26:159-169

Google Scholar

16. Neumaier F, Zlatopolskiy BD, Neumaier B. Drug pene- tration into the central nervous system: Pharmacokinetic concepts and in vitro model systems. Pharmaceutics 2021;13:1542

Google Scholar

17. Laniado-Laborín R, Cabrales-Vargas MN. Amphotericin B: side effects and toxicity. Rev Iberoam Micol 2009;26: 223-227

Google Scholar

18. França FD, Ferreira AF, Lara RC, Rossoni JV Jr, Costa DC, Moraes KC, et al. Alteration in cellular viability, pro-inflammatory cytokines and nitric oxide production in nephrotoxicity generation by amphotericin B: involve- ment of PKA pathway signaling. J Appl Toxicol 2014;34: 1285-1292

Google Scholar

19. Clarke F, Grenfell A, Chao S, Richards H, Korman T, Rogers B. Use of echinocandin outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy for the treatment of infection caused by Candida spp.: utilization, outcomes and impact of a change to weekly dosing. J Antimicrob Chemother 2024;79:2896-2900

Google Scholar

20. Donders G, Sziller IO, Paavonen J, Hay P, de Seta F, Bohbot JM, et al. Management of recurrent vulvo- vaginal candidosis: Narrative review of the literature and European expert panel opinion. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2022;12:934353

Google Scholar

21. Mohammadi G, Fathian-Kolahkaj M, Mohammadi P, Adibkia K, Fattahi A. Preparation, physicochemical char- acterization and antifungal evaluation of amphotericin B-loaded PLGA-PEG-galactosamine nanoparticles. Adv Pharm Bull 2021;11:311-317

Google Scholar

22. Nagavarma BVN, Yadav HKS, Ayaz A, Vasudha LS, Shivakumar HG. Different techniques for preparation of polymeric nanoparticles: a review. Asian J Pharm Clin Res 2012;5:16-23

Google Scholar

23. Bhatt P, Lalani R, Vhora I, Patil S, Amrutiya J, Misra A, et al. Liposomes encapsulating native and cyclodextrin enclosed paclitaxel: enhanced loading efficiency and its pharmacokinetic evaluation. Int J Pharm 2017;536:95-107

Google Scholar

24. Lee JH, Yeo Y. Controlled drug release from pharma- ceutical nanocarriers. Chem Eng Sci 2015;125:75-84

Google Scholar

25. Srivastava R, Rawat AKS, Mishra MK, Patel AK. Advance- ments in nanotechnology for enhanced antifungal drug delivery: A comprehensive review. Infect Disord Drug Targets 2024;24:e021123223053

Google Scholar

26. Goyal R, Macri LK, Kaplan HM, Kohn J. Nanoparticles and nanofibers for topical drug delivery. J Control Release 2016;240:77-92

Google Scholar

27. Rangari AT, Ravikumar P. Polymeric nanoparticles based topical drug delivery: an overview. Asian J Biomed Pharm Sci 2015;5:5-12

28. Siegel RA, Rathbone MJ. Overview of controlled release mechanisms. In: Fundamentals and applications of con- trolled release drug delivery. New York (NY): Springer; 2011:19-43

Google Scholar

29. Rudolph N, Charbe N, Plano D, Shoyaib AA, Pal A, Boyce H, et al. A physiologically based biopharma- ceutics modeling (PBBM) framework for characterizing formulation-dependent food effects: Paving the road towards fed state virtual BE studies for itraconazole amorphous solid dispersions. Eur J Pharm Sci 2025;209: 107047

Google Scholar

30. Aigner M, Lass-Flörl C. Encochleated amphotericin B: is the oral availability of amphotericin B finally reached? J Fungi (Basel) 2020;6:66

Google Scholar

31. Fairuz S, Nair RS, Billa N. Orally administered amphotericin B nanoformulations: physical properties of nanoparticle carriers on bioavailability and clinical relevance. Pharma- ceutics 2022;14:1823

Google Scholar

32. Dalton LM, Kauffman CA, Miceli MH. Oral lipid nano- crystal amphotericin B (MAT2203) for the treatment of invasive fungal infections. Open Forum Infect Dis 2024; 11:ofae346

Google Scholar

33. Shirkhani K, Teo I, Armstrong-James D, Shaunak S. Nebulised amphotericin B-polymethacrylic acid nano- particle prophylaxis prevents invasive aspergillosis. Nano- medicine 2015;11:1217-1226

Google Scholar

34. Ayatollahi Mousavi SA, Mokhtari A, Barani M, Izadi A, Amirbeigi A, Ajalli N, et al. Advances of liposomal mediated nanocarriers for the treatment of dermatophyte infections. Heliyon 2023;9:e18960

Google Scholar

35. Yetisgin AA, Cetinel S, Zuvin M, Kosar A, Kutlu O. Therapeutic nanoparticles and their targeted delivery applications. Molecules 2020;25:2193

Google Scholar

36. D'Souza S. A review of in vitro drug release test methods for nano-sized dosage forms. Adv Pharm 2014;2014: 304757

Google Scholar

37. Yoo J, Park C, Yi G, Lee D, Koo H. Active targeting strategies using biological ligands for nanoparticle drug delivery systems. Cancers (Basel) 2019;11:640

Google Scholar

38. Behzadi S, Serpooshan V, Tao W, Hamaly MA, Alkawareek MY, Dreaden EC, et al. Cellular uptake of nanoparticles: journey inside the cell. Chem Soc Rev 2017;46:4218-4244

Google Scholar

39. Zarif L, Graybill JR, Perlin D, Najvar L, Bocanegra R, Mannino RJ. Antifungal activity of amphotericin B coch- leates against Candida albicans infection in a mouse model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2000;44:1463-1469

Google Scholar

40. Lu C, Zhao Y, Park S, Mannino R, Perlin D. Efficacy of oral cochleate-amphotericin B for the prevention of invasive candidiasis in neutropenic mice. Matinas Bio- Pharma scientific presentations and publications; 2018

Google Scholar

41. Szebeni J. Complement activation-related pseudoallergy: a stress reaction in blood triggered by nanomedicines and biologicals. Mol Immunol 2014;61:163-173

Google Scholar

42. Boswell GW, Buell D, Bekersky I. AmBisome (liposomal amphotericin B): a comparative review. J Clin Pharmacol 1998;38:583-592

Google Scholar

43. Sesana AM, Monti-Rocha R, Vinhas SA, Morais CG, Dietze R, Lemos EM. In vitro activity of amphotericin B cochleates against Leishmania chagasi. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2011;106:251-253

Google Scholar

44. Crommelin DJA, van Hoogevest P, Storm G. The role of liposomes in clinical nanomedicine development: what now? Now what? J Control Release 2020;318:256-263

Google Scholar

45. Cassano R, Ferrarelli T, Mauro MV, Cavalcanti P, Picci N, Trombino S. Preparation, characterization and in vitro activities evaluation of solid lipid nanoparticles based on PEG-40 stearate for antifungal drugs vaginal delivery. Drug Deliv 2016;23:1037-1046

Google Scholar

46. Jain S, Jain S, Khare P, Gulbake A, Bansal D, Jain SK. Design and development of solid lipid nanoparticles for topical delivery of an antifungal agent. Drug Deliv 2010; 17:443-451

Google Scholar

47. Mohanty B, Majumdar DK, Mishra SK, Panda AK, Patnaik S. Development and characterization of itraconazole-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles for ocular delivery. Pharm Dev Technol 2015;20:458-464

Google Scholar

48. Padarthi PK, Kalvimoorthi V, Challa RR, Vallamkonda B, Grandhe N, Dogiparthi LK, et al. Non-Ionic surfactant vesicles (Niosomes): Structure, functions, classification and its advances in enhanced drug delivery. Recent Adv Drug Deliv Formul 2025;19:87-104

Google Scholar

49. Ascenso A, Raposo S, Batista C, Cardoso P, Mendes T, Praça FG, et al. Development, characterization, and skin delivery studies of related ultradeformable vesicles: transfersomes, ethosomes, and transethosomes. Int J Nanomedicine 2015;10:5837-5851

Google Scholar

50. Amaral AC, Bocca AL, Ribeiro AM, Nunes J, Peixoto DL, Simioni AR, et al. Amphotericin B in poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) and dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA) nano- particles against paracoccidioidomycosis. J Antimicrob Chemother 2009;63:526-533

Google Scholar

51. Bugno J, Hsu H, Hong S. Tweaking dendrimers and dendritic nanoparticles for controlled nano-bio interactions: potential nanocarriers for improved cancer targeting. J Drug Target 2015;23:642-650

Google Scholar

52. Subedi YP, AlFindee MN, Takemoto JY, Chang CT. Antifungal amphiphilic kanamycins: new life for an old drug. MedChemComm 2018;9:909-919

Google Scholar

53. Lima AL, Gratieri T, Cunha-Filho M, Gelfuso GM. Poly- meric nanocapsules: a review on design and production methods for pharmaceutical purpose. Methods 2022; 199:54-66

Google Scholar

54. Ahmad A, Wei Y, Syed F, Tahir K, Taj R, Khan AU, et al. Amphotericin B-conjugated biogenic silver nanoparticles as an innovative strategy for fungal infections. Microb Pathog 2016;99:271-281

Google Scholar

55. Hussain MA, Ahmed D, Anwar A, Perveen S, Ahmed S, Anis I, et al. Combination therapy of clinically approved antifungal drugs is enhanced by conjugation with silver nanoparticles. Int Microbiol 2019;22:239-246

Google Scholar

56. Frank LA, Onzi GR, Morawski AS, Pohlmann AR, Guterres SS, Contri RV. Chitosan as a coating material for nanoparticles intended for biomedical applications. React Funct Polym 2020;147:104459

Google Scholar

57. Mehta P, Sharma M, Devi M. Hydrogels: an overview of its classifications, properties, and applications. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater 2023;147:106145

Google Scholar

58. Zumbuehl A, Ferreira L, Kuhn D, Astashkina A, Long L, Yeo Y, et al. Antifungal hydrogels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007;104:12994-12998

Google Scholar

59. Vera-González N, Deusenbery C, LaMastro V, Shukla A. Fungal enzyme-responsive hydrogel drug delivery plat- form for triggered antifungal release. Adv Healthc Mater 2024;13:e2401157

60. Snyder SS, Rock CA, Millenbaugh NJ. Antifungal peptide-loaded alginate microfiber wound dressing evaluated against Candida albicans in vitro and ex vivo. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 2024;205:114578

Google Scholar

61. Fu X, Zhang C, Lin X, Zheng X, Liu Q, Jin Y. Safety and effectiveness of high-dose liposomal amphotericin B: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Altern Ther Health Med 2024;30:127-135

Google Scholar

62. Maqsood MH, Alam M, Atar D, Birnbaum Y. Efficacy of long-term oral beta-blocker therapy in patients who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 2021;77:87-93

Google Scholar

63. Rijnders BJ, Cornelissen JJ, Slobbe L, Becker MJ, Doorduijn JK, Hop WC, et al. Aerosolized liposomal amphotericin B for the prevention of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis during prolonged neutropenia: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis 2008;46:1401-1408

Google Scholar

64. Study in Adult Asthmatic Patients With Allergic Broncho- pulmonary Aspergillosis (NCT03960606). ICH GCP/ ichgcp.net clinical trials registry. Published 2019 May 14. Accessed 2025 Aug 10. Available from: https:// ichgcp.net/clinical-trials-registry/NCT03960606

65. Tewari AK, Mohanty AK, Mishra A, Mandal TK. Drug delivery challenges and formulation aspects of nanotechnology-based drug delivery. In: Grumezescu AM, ed. Design of nanostructures for theranostics applications. Elsevier; 2018:159-206

66. Fernando LD, Zhao W, Gautam I, Ankur A, Wang T. Polysaccharide assemblies in fungal and plant cell walls explored by solid-state NMR. Structure 2023;31:1375-1385

Google Scholar

67. Liu N, Wang X, Wang Z, Kan Y, Fang Y, Gao J, et al. Nanomaterials-driven in situ vaccination: a novel frontier in tumor immunotherapy. J Hematol Oncol 2025;18:45

Google Scholar

68. Corduas F, Mancuso E, Lamprou DA. Long-acting implan- table devices for the prevention and personalised treat- a ment of infectious, inflammatory and chronic diseases. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol 2020;60:101952

Google Scholar

Congratulatory MessageClick here!