pISSN : 3058-423X eISSN: 3058-4302

Open Access, Peer-reviewed

pISSN : 3058-423X eISSN: 3058-4302

Open Access, Peer-reviewed

Trang Thi Quynh Tran,Kyung-Hwa Nam,Seok-Kweon Yun,Jin Park

10.17966/JMI.2025.30.3.113 Epub 2025 October 01

Abstract

Scabies is typically characterized by pruritic lesions. In immunocompetent adults, these most commonly affect the interdigital spaces, wrists, and trunk, while sparing the face and scalp. However, the incidence of atypical presentations involving the scalp may be under-reported, particularly in older adults and institutionalized patients. We report a case of a 90-year-old woman with a prolonged history of scalp pruritus. Unrecognized scalp involvement contributed to the therapeutic failure of scabies treatment. Upon examination, scabies with scalp involvement was confirmed using dermoscopy and skin scraping. The patient was treated with oral ivermectin. Topical permethrin was also applied thoroughly from head-to-toe, including the scalp. This case highlights the critical importance of a comprehensive head-to-toe examination, the use of dermoscopy for diagnostic accuracy, and complete topical treatment, particularly in high-risk populations.

Keywords

Dermoscopy Permethrin Scabies Scalp

Scabies is a common epidermal infestation of Sarcoptes scabiei var. hominis mites. It is typically transmitted through direct skin-to-skin contact, but can also be transmitted indir- ectly via fomites1. Clinically, scabies manifests as pruritic lesions, excoriations, and eczematous dermatitis. It predominantly affects skinfold areas, causing intense pruritus that disrupts sleep. In immunocompetent adults, scabies generally affects the body from the neck down, sparing the face and scalp. However, in infants, older adults, and immunocompromised patients, atypical presentations involving the scalp may occur. However, these are often underdiagnosed or misdiagnosed as other dermatological conditions1.

A diagnosis of scabies is made based on clinical symptoms and the results of diagnostic imaging, such as microscopy or dermoscopy, which is used to identify the presence of scabies mites, eggs, or scybala. Dermatoscopy, particularly with ultraviolet dermatoscopes, enhances diagnostic accuracy by providing clearer, more detailed visualization of the char- acteristic findings2,3. The treatment for scabies is topical permethrin or oral ivermectin, both of which eliminate the mites and their eggs. Topical treatments are generally applied from the neck down to the feet, covering all skin areas. This is left on the skin for a minimum of 8 hours4.

While classical scabies in adults tends to spare the scalp, an increasing number of studies have reported atypical pre- sentations involving the scalp. In this case study, we report a case of scabies that affected the scalp in an older woman, which was inadequately treated due to the incomplete application of topical therapy.

A 90-year-old woman was referred to our dermatology department with a 9-month history of severe pruritus, which began during a period of prolonged hospitalization at a nursing facility. Despite multiple treatments for suspected scabies with topical permethrin and crotamiton, the patient's symptoms persisted. Most recently, a topical corticosteroid solution had been used, but had failed to provide any relief. The patient's medical history included hypertension and dementia.

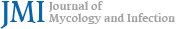

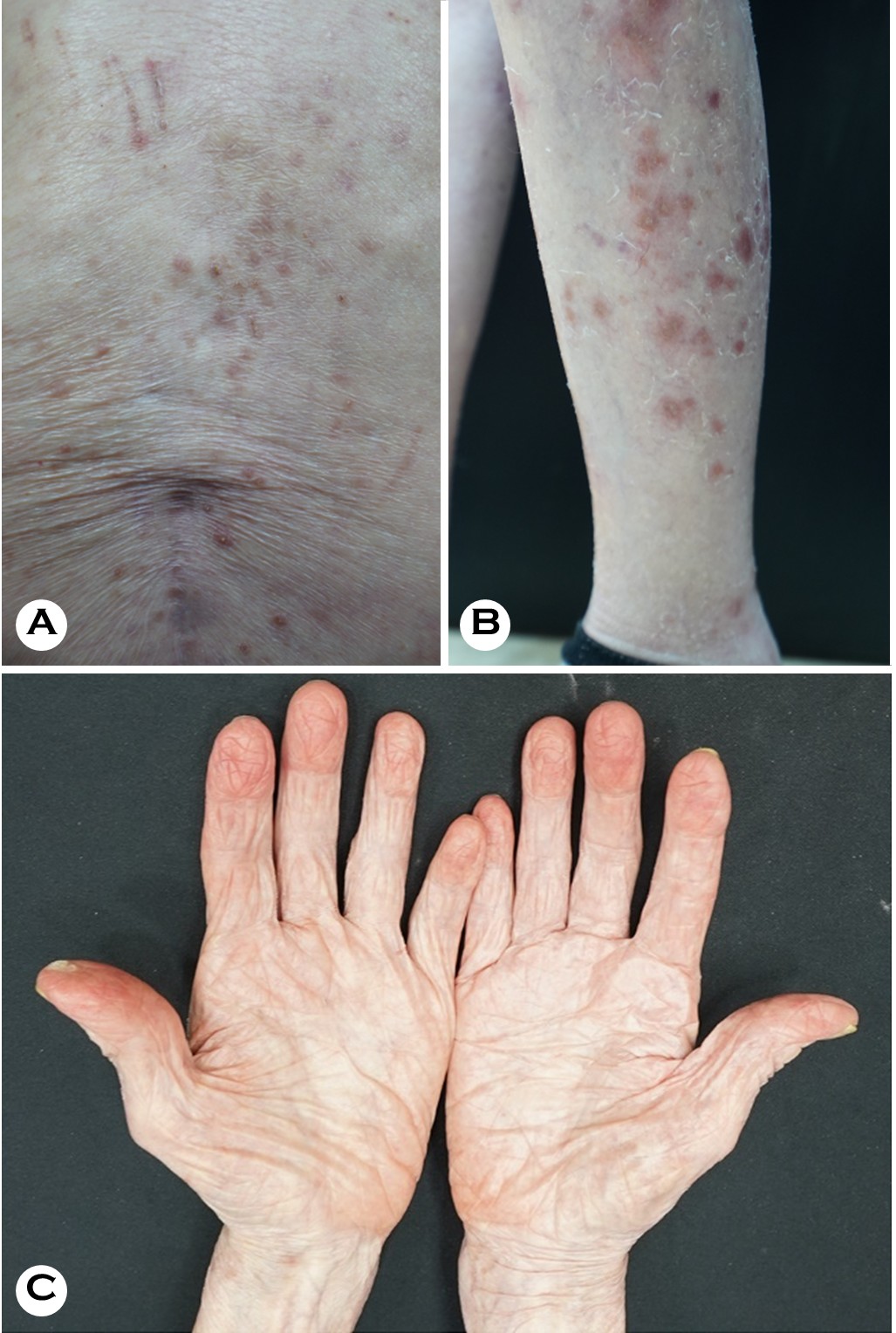

Physical examination of the patient revealed numerous erythematous papules, linear excoriations, and xerotic patches on the trunk and extremities (Fig. 1A and 1B). Notably, there were no burrows or papules between the fingers, on the wrists, or in the axilla or groin (Fig. 1C). Skin scrapings from the scaly lesions on her trunk and finger web spaces showed no scabies mites under microscopic examination. However, there were prominent erythematous papules and scaling lesions on the scalp, which were visible to the naked eye (Fig. 2A). Dermoscopy revealed interfollicular scaling, black dots, broken hairs, and diagnostic signs of scabies, including the hang-glider sign (triangular mite head) and the jet with contrail sign (Figs. 2B and 2C).

Laboratory tests were performed, including a complete blood count and a metabolic panel. Other than a mildly elevated serum IgE level of 162.0 IU/mL, the results were within normal limits. Skin scrapings from the scalp confirmed the presence of Sarcoptes scabiei. The prescribed treatment was oral ivermectin (3 mg/kg on days 0, 1, 7, 8, and 14) and topical 5% permethrin, which was to be applied twice a week over the entire body, including the scalp. Follow-up at 2 and 4 weeks showed complete resolution without recurrence.

The typical clinical presentation of scabies is characteristic burrows and erythematous papules, which are focused in the interdigital web spaces, on the inner wrists, the periumbilical areas, the axillae, and the genitals. These site preferences indicate that scabies mites thrive in areas with relatively higher skin temperature and a thin stratum corneum, and avoid regions with a high density of pilosebaceous units5.

In contrast to this standard presentation, older adults, infants, and immunodeficient patients may exhibit hyperkeratotic scaly lesions (crusted scabies) or atypical lesion distribution. In such cases, the scalp, face, palms, and soles may be affected3. In young children and older adults, the scalp is more sus- ceptible to infestation due to reduced inhibitory effects of sebum and age-related differences in the density of hair follicles. These atypical scabies cases may be underdiagnosed or misdiagnosed due to symptoms that overlap with those seen in other dermatological conditions, such as eczema, seborrheic dermatitis, and psoriasis6,7. This case also under- scores the diagnostic challenges presented by scalp scabies, which is a rare manifestation of the condition in immuno- competent adults. Our patient's scalp lesions had initially been misdiagnosed as seborrheic dermatitis and treated with corticosteroids, delaying the correct diagnosis. While scalp involvement is more commonly observed in crusted scabies or pediatric patients1,8, reports of scabies with scalp involvement in older adults are becoming more frequent. Chiu and Lan have reported a case of crusted scabies with exclusive scalp involvement in an institutionalized older woman, challenging the conventional notion that the scalp is usually spared in adults9. Duran et al. reported cases of scabies similar to ours, which mimicked seborrheic dermatitis in immunosuppressed children. In these patients, scalp scaling was the predominant feature10. Huang et al. have described a case of crusted scabies on the scalp of an older woman that was also initially mis- diagnosed as seborrheic dermatitis11. Therefore, it is advisable to perform a thorough head-to-toe skin examination in patients presenting with generalized pruritus, particularly those from vulnerable patient populations. In such instances, dermoscopy can serve as a rapid and effective diagnostic tool, particularly for the confirmation of scabies in skin regions such as the scalp that are prone to overlapping secondary lesions (crust, scale, oily scale, erosions, etc.), and therefore more subject to diagnostic confusion12. The use of ultraviolet dermoscopy with our patient facilitated the identification of classical scabietic burrows and mites by highlighting distinct fluorescent reflection patterns and aiding in the detection of otherwise difficult-to-see lesions13.

Topical 5% permethrin is the first-line treatment for scabies. Alternative treatments include oral ivermectin, which is typically employed when the topical treatment is unsuitable or ineffective, especially in patients with crusted lesions. Topical permethrin is generally applied from the neck down to the feet, excluding the scalp. However, in infants, young children, and older adults with scalp or facial involvement, it should be applied over the entire body, including the face and scalp4,14. The primary causes of scabies treatment failure are improper treatment, the use of topical steroids, and in- adequate disinfection of clothing and bedding. In our case, repeated permethrin applications had been ineffective, pos- sibly due to the exclusion of the scalp. In atypical cases, the scalp may harbor untreated mites, allowing recurring or ongoing infestation. This case underscores the importance of comprehensive treatment, including the scalp, to ensure complete eradication and prevent recurrence in high-risk patients.

This case highlights the need for a high index of suspicion for scabies in older patients with atypical pruritic scalp lesions, especially those with a history of institutionalization or pro- longed corticosteroid use. A thorough head-to-toe skin examination, dermoscopy, and, following a positive diagnosis, comprehensive treatment that includes the scalp and neck, are crucial for effective management and recurrence pre- vention. Our findings suggest a need for updated scabies treatment guidelines to routinely include scalp application of topical therapies in high-risk populations.

References

1. Wheat CM, Burkhart CN, Burkhart CG, Cohen BA. Scabies, other mites, and pediculosis. In: Kang S, Amagai M, Bruckner AL, Enk AH, Margolis DJ, McMichael AJ, et al., editors. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology, 9e. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education; 2019

2. Uzun S, Durdu M, Yürekli A, Mülayim MK, Akyol M, Velipaşaoğlu S, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of scabies. Int J Dermatol 2024; 63:1642-1656

Google Scholar

3. Park J, Kwon SH, Lee YB, Kim HS, Jeon JH, Choi GS. Clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and treat- ment of scabies in Korea: Part 1. Epidemiology, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis — a secondary publication. Ewha Med J 2024;47:e73

Google Scholar

4. Park J, Kwon SH, Lee YB, Kim HS, Jeon JH, Choi GS. Clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and treat- ment of scabies in Korea: Part 2. Treatment and prevention — a secondary publication. Ewha Med J 2024;47:e72

Google Scholar

5. Sunderkötter C, Feldmeier H, Fölster-Holst R, Geisel B, Klinke-Rehbein S, Nast A, et al. S1 guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of scabies - short version. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2016;14:1155-1167

Google Scholar

6. Khurana ABS, Muddebihal A, Ahuja A. Severe, recurrent crusted scabies in a psoriatic on methotrexate. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2022;106:1581-1582

Google Scholar

7. Wu X, Yang F, Zhang R. Frequent misdiagnosis of scabies as eczema in China: a descriptive study of 23 cases. Int J Gen Med 2024;17:1615-1623

Google Scholar

8. Hasan T, Krause VL, James C, Currie BJ. Crusted scabies: a 2-year prospective study from the Northern Territory of Australia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2020;14:e0008994

Google Scholar

9. Chiu HH, Lan CE. Crusted scabies with scalp involvement in an institutionalized elderly. Indian J Sex Transm Dis AIDS 2020;41:137-138

Google Scholar

10. Duran C, Tamayo L, de la Luz Orozco M, Ruiz-Maldonado R. Scabies of the scalp mimicking seborrheic dermatitis in immunocompromised patients. Pediatr Dermatol 1993; 10:136-138

Google Scholar

11. Huang YC, Chen MJ, Shih PY. Crusted scabies on the scalp mimicking seborrheic dermatitis. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2012;54:882

Google Scholar

12. Park JH, Kim CW, Kim SS. The diagnostic accuracy of dermoscopy for scabies. Ann Dermatol 2012;24:194-199

Google Scholar

13. Yürekli A, Muslu İ, Pektaş SD, Alataş ET, Aydoğdu CT, Daşgin D. Using ultraviolet dermoscopy in diagnosing scabies. Exp Dermatol 2023;32:1996-1999

Google Scholar

14. Currie BJ, McCarthy JS. Permethrin and ivermectin for scabies. N Engl J Med 2010;362:717-725

Google Scholar

Congratulatory MessageClick here!