pISSN : 3058-423X eISSN: 3058-4302

Open Access, Peer-reviewed

pISSN : 3058-423X eISSN: 3058-4302

Open Access, Peer-reviewed

Nanda Daiva Putra,Sylvia Anggraeni,Evy Ervianti,Linda Astari,Yuri Widia

10.17966/JMI.2024.29.3.170 Epub 2024 October 11

Abstract

Mucormycosis is a rare and life-threatening fungal infection that predominantly affects immunocompromised individuals, particularly those with poorly controlled diabetes mellitus. Achieving an accurate diagnosis remains a significant challenge in clinical practice. We report a case of mucormycosis in a 25-year-old woman who presented with an altered mental status and a 5 × 2 cm necrotic lesion on the left nasal septum, characterized by indistinct borders, during admission. Prolonged diagnostic investigations ultimately led to the identification of nasal mucormycosis attributable to Rhizomucor pusillus, a rare species within the Mucorales order, which complicates the diagnostic process. Unfortunately, the patient's clinical condition rapidly deteriorated, resulting in her demise prior to the administration of systemic antifungal therapy. Although the comprehensive evaluations facilitated the identification of the causative agent, the time required for this process did not favor the patient's prognosis. The atypical symptoms, swift progression, and infrequent occurrence of mucormycosis underscore the critical importance of its timely and accurate diagnosis to ensure favorable patient outcomes. Proper identification of the pathogen and immediate administration of therapeutic interventions can considerably enhance the likelihood of patient recovery and survival.

Keywords

Deep mycosis Diabetes mellitus Mucormycosis Rhizomucor

Mucormycosis, a rare, life-threatening fungal infection, is often misdiagnosed due to its initial nonspecific symptoms, which can be mistaken for more common and less severe conditions1,2. Its primary causative agents include Rhizopus oryzae (70%), Mucor species (e.g., M. circinelloides), and Rhizomucor species (e.g., R. pusillus)3. These insidious patho- gens can rapidly invade host tissues, leading to severe patient outcomes if not promptly identified and treated4. The delays in its diagnosis and treatment can result in rapid dissemination of the infection, causing extensive tissue damage and systemic complications.

Early diagnosis is crucial for promptly initiating antifungal therapy and performing aggressive surgical debridement to remove necrotic tissue5. Healthcare providers must maintain a high level of awareness and suspicion, especially in patients at an increased risk for developing mucormycosis. The present paper describes a case of delayed diagnosis of nasal mucormycosis, which progressed swiftly to severe sepsis and neurological complications, ultimately leading to the patient's death.

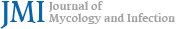

A 25-year-old woman with an altered mental status and a rapidly worsening nasal wound, which was initially attributed to nasogastric tube insertion, was admitted to the emergency department of Dr. Soetomo General Hospital. The wound's condition markedly worsened over a few days. The patient, with a history of diabetes mellitus and ongoing insulin therapy, presented with a necrotic nasal wound on the left septum, approximately 5 × 2 cm, with indistinct borders, black eschar, and multiple erosions (Fig. 1A).

Laboratory tests revealed leukocytosis (12,160/μL), hyper- natremia (sodium 150 mEq/L), and elevated serum creatinine (2.9 mg/dL) and alanine aminotransferase (98 U/L) levels. Her blood glucose level was initially 148 mg/dL, increasing to 451 mg/dL 2 days later, with a hemoglobin A1C level of 12.9%. Her procalcitonin and C-reactive protein levels were markedly high at 8.0 and 9.82 mg/dL, respectively. Blood gas analysis confirmed ketoacidosis.

Her nasal wound was treated with NaCl 0.9% wet com- presses and fusidic acid cream (Fig. 1B). Owing to the deteri- oration of her clinical condition, she received critical care in the intensive care unit with ventilator support. Cefoperazone 1 g every 12 hours was given as sepsis management. Insulin was administered 4 units every hour via syringe pump to normalize her blood glucose level. Other interventions were also administered to stabilize her condition while the under- lying cause of her condition was being investigated.

Her condition was reviewed by the Plastic Surgery and ENT departments for specialized evaluation and management. Following this interdisciplinary consultation, the Plastic Surgery team performed debridement of the nasal wound in the subsequent days (Fig. 1C).

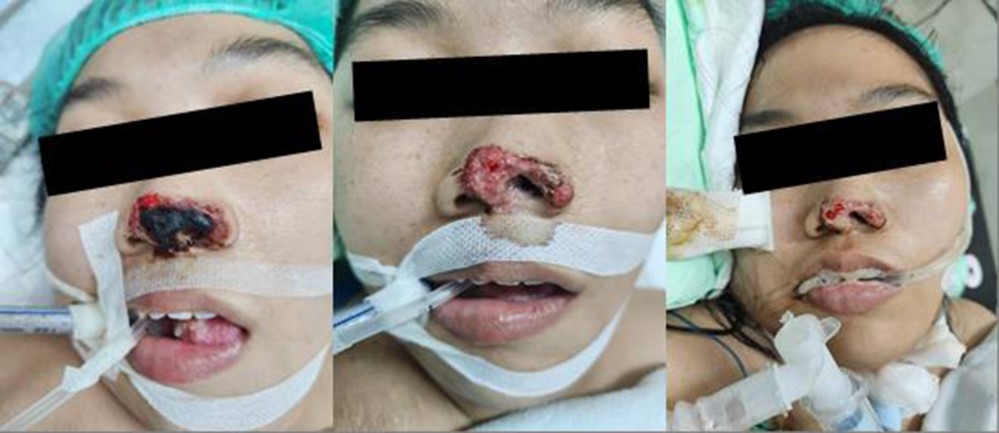

A cranial computed tomography scan revealed brain edema and left maxillary sinusitis but no infarction, hemorrhage, or space-occupying lesions were noted within the brain paren- chyma. Gram staining of the scraped specimen identified hyphae with irregular diameters and right-angle branching (Fig. 2A). Periodic acid-Schiff staining, showing broad, non-septate, irregular hyphae with non-dichotomous branching patterns, further confirmed the diagnosis of mucormycosis (Fig. 2B).

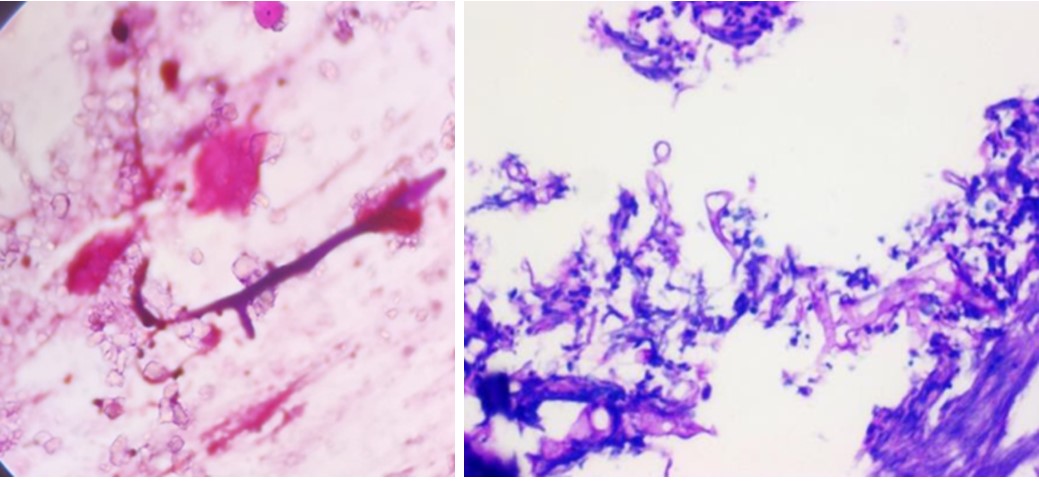

On the third day of hospitalization, wound culture results revealed colonies with a very fluffy, cotton candy-like texture. The colonies were initially gray, but they darkened to a brownish hue with age, while the reverse side was white (Fig. 3A). Microscopic examination showed broad, non-septate hyphae with irregular branching patterns, including non-dichotomous branches sometimes forming right angles (Fig. 3B). Additionally, the specimen exhibited long sporangio- phores, with rhizoids absent at the junction of the stolon and sporangiophore (Fig. 3C).

The patient was diagnosed with nasal mucormycosis and developed complications, such as brain edema, acute kidney injury, septic shock, and diabetic ketoacidosis. Despite our attempts to manage these conditions, the patient's health declined rapidly, and regrettably, the patient passed away on the fifth day of hospitalization before antifungal therapy could be initiated.

Mucormycosis, also known as zygomycosis, is a severe and potentially fatal fungal infection caused by fungi from the class Zygomycetes and the order Mucorales. The fungi can enter the body through inhalation of their spores, ingestion, or inoculation into wounds. This infection primarily affects immunocompromised individuals, making this fungus an opportunistic pathogen. The key genera involved include R. oryzae (70%), Mucor spp., and Rhizomucor spp. Owing to their small size (3~5 μm), Rhizomucor spores can easily be- come airborne and inhaled6.

In our case, the patient's uncontrolled diabetes played a critical role in the development of mucormycosis through nasal wound inoculation. The patient's hyperglycemia and acidosis compromised her immune response, impairing chemotaxis and phagocytosis needed to clear fungal spores and hyphae. Additionally, the fungus Rhizopus contains ketone reductase, which facilitates growth in acidic, glucose-rich environments, such as in cases of diabetic ketoacidosis. This adaptation allows the pathogen to thrive when the host defenses are weakened2. Mucormycosis has a particular affinity for angioinvasion, which can lead to systemic infection, thrombosis, and considerable tissue necrosis4.

In our patient, mucormycosis initially affected the nasal area and skin, leading to a diagnosis of cutaneous mucormycosis. However, the potential risk of progression to rhino-orbital-cerebral mucormycosis (ROCM) and angioinvasion raised concerns about a potential central nervous system involvement. The presence of altered consciousness, brain edema, and severe sepsis indicates possible dissemination of the infection to the vital organs, including the brain. Given the diagnosis of cutaneous mucormycosis in conjunction with neurological symptoms, the likelihood of mucormycosis affecting the brain and contributing to severe sepsis should be considered. However, to definitively establish a diagnosis of ROCM, further examinations and diagnostic evaluations are essential7.

Cutaneous mucormycosis must be differentiated from other soft tissue infections, including necrotizing fasciitis, pyomyositis, and cellulitis, and fungal infections, including aspergillosis or candidiasis. Histopathological examination and fungal culture are crucial for making an accurate diagnosis. Histopathology reveals the characteristic fungal morphology, whereas cultures confirm the organism and guide antifungal therapy5,8.

Effective management of cutaneous mucormycosis involves a multidisciplinary approach, combining surgical debridement and antifungal therapy6. The prompt initiation of systemic antifungal therapy is essential to address the invasive nature of the infection. Liposomal amphotericin B is typically the first-line treatment, with posaconazole and isavuconazole as the alternative options. Additionally, managing the underlying conditions, such as hyperglycemia, is critical for improving patient outcomes6,9.

Mucormycosis presents a great diagnostic and therapeutic challenge due to its rapid progression, especially in patients with uncontrolled diabetes, as demonstrated in the present case. Accurate and timely diagnosis, including the identi- fication of the specific fungal species, is crucial for evaluating disease progression and selecting the appropriate antifungal treatments, thus facilitating comprehensive disease manage- ment. Broad-spectrum antifungal therapy is a vital, life-saving intervention for mucormycosis, and surgical debridement, when feasible, is essential to reduce the fungal burden and enhance the effectiveness of antifungal treatment4,10. Despite the advancements in diagnosis and therapy, the prognosis for cutaneous mucormycosis remains guarded, particularly in cases with a delayed diagnosis or extensive tissue involve- ment. Early recognition of the infection and prompt initiation of treatment are critical to improve the patients' survival outcomes. The combination of antifungal therapy and surgical intervention is associated with a higher survival rate (70%), as compared to surgical management alone (57%) or anti- fungal treatment alone (61%)11.

Mucormycosis presents a considerable diagnostic challenge, especially in its facial, intracranial, and nasal forms. The condition's subtle symptoms, rapid progression, and relative rarity underscore the need for prompt diagnosis and intervention to prevent the development of severe outcomes, particularly in high-risk populations such as individuals with poorly con- trolled diabetes. By increasing awareness among healthcare providers, promoting interdisciplinary collaboration, and maintaining a vigilant medical approach, we can more effectively address the complexities of mucormycosis. This proactive strategy is crucial in managing this serious infection, ultimately improving the patients' chances of recovery and survival.

References

1. Skiada A, Lass-Floerl C, Klimko N, Ibrahim A, Roilides E, Petrikkos G. Challenges in the diagnosis and treatment of mucormycosis. Med Mycol 2018;56:S93-101

Google Scholar

2. Ponnaiyan D, Anitha CM, Prakash PSG, Subramanian S, Rughwani RR, Kumar G, et al. Mucormycosis diagnosis revisited: current and emerging diagnostic methodologies for the invasive fungal infection (Review). Exp Ther Med 2022;25:47

Google Scholar

3. Hernandez JL, Buckley CJ. Mucormycosis. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, 2023

4. Singh AK, Singh R, Joshi SR, Misra A. Mucormycosis in COVID-19: a systematic review of cases reported world- wide and in India. Diabetes Metab Syndr 2021;15:102146

Google Scholar

5. Reid G, Lynch JP 3rd, Fishbein MC, Clark NM. Mucor- mycosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2020;41:99-114

Google Scholar

6. Walsh TJ, Hospenthal DR, Petraitis V, Kontoyiannis DP. Necrotizing mucormycosis of wounds following combat injuries, natural disasters, burns, and other trauma. J Fungi (Basel) 2019;5:57

Google Scholar

7. Smith BE. Focal and entrapment neuropathies. Handb Clin Neurol 2014;126:31-43

Google Scholar

8. Walsh TJ, Hayden RT, Larone DH. Larone's medically important fungi: a guide to identification. Washington: ASM Press, 2018

Google Scholar

9. Alastruey-Izquierdo A, Castelli MV, Cuesta I, Monzón A, Cuenca-Estrella M, Rodriguez-Tudela JL. Activity of posa- conazole and other antifungal agents against Mucorales strains identified by sequencing of internal transcribed spacers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2009;53:1686-1689

Google Scholar

10. Passi N, Wadhwa AC, Naik S. Radiological spectrum of invasive mucormycosis in COVID-19. BJR Case Rep 2022; 7:20210111

Google Scholar

11. Pai V, Sansi R, Kharche R, Bandili SC, Pai B. Rhino-orbito-cerebral mucormycosis: pictorial review. Insights Imaging 2021;12:167

Google Scholar

Congratulatory MessageClick here!