pISSN : 3058-423X eISSN: 3058-4302

Open Access, Peer-reviewed

pISSN : 3058-423X eISSN: 3058-4302

Open Access, Peer-reviewed

Mohammed Ashraf Ali Namaji,Prerna Godara,Kundan Tandel,Sanjay Pratap Singh,R Mahesh Reddy,Raghavendra Huchchannavar

10.17966/JMI.2024.29.2.61 Epub 2024 July 07

Abstract

Background: Candiduria is a common phenomenon among hospitalized patients, particularly those in intensive care units (ICUs), wherein multiple predisposing factors such as comorbidities, indwelling urinary catheters, and antimicrobial exposure contribute to its prevalence.

Objective: This study aims to investigate the epidemiological trends and antifungal susceptibility patterns of Candida spp. isolated from urine samples of patients at a tertiary care center in Western Maharashtra, India.

Methods: Of the 7,642 urine samples received between 01 June 2022 to 31 May 2023, 142 samples (9%) displayed the growth of Candida species. Upon retesting samples from these patients, only 70 true positive results were identified. All the isolates were detected via VITEK MS (bioMerieux, France), while antifungal susceptibility testing (AFST) was conducted using the VITEK 2 Compact with an AST-YS08 card.

Results: The most common isolate was Candida tropicalis (50%), followed by Candida albicans (25.7%). Rare Candida species (e.g., Candida ciferrii, Candida kefyr, Candida metapsilosis, Candida utilis) collectively contributed to 7.1% of all Candida species. The results of the AFST revealed a high sensitivity to amphotericin B and echinocandins. Fluconazole resistance was observed in 6% of the isolates. Candida ciferrii demonstrated a distinct pattern, indicating a statistically significant association (p = 0.015) when the patient had two or more comorbidities and resistance to azoles, which was statistically significant (p-values for fluconazole (p = 0.015), voriconazole (p = 0.004), and flucytosine (p = 0.002)) when compared with other Candida species.

Conclusion: Resistance trends in India have been changing with increased fluconazole-resistant Candida strains being frequently isolated, emphasizing the importance of customized therapeutic strategies based on culture and sensitivity reports.

Keywords

Candida ciferrii Candida ciferrii resistance Candiduria Fluconazole resistance Rare Candida isolates UTI

Candiduria, a relatively rare occurrence in healthy individuals, has become a common phenomenon among hospitalized patients, particularly those in ICUs, wherein multiple predis- posing factors, such as diabetes mellitus, indwelling urinary catheters, and antimicrobial exposure, contribute to its pre- valence. Asymptomatic candiduria does not require treatment, except in patients with specific conditions that may predispose them to candidemia or disseminated infections1,2.

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are classified anatomically as upper UTI (e.g., pyelonephritis) or lower UTI (e.g., cystitis, urethritis). Although Candida cystitis presents as an increased frequency of urination, hematuria, and dysuria, most cases of Candida pyelonephritis present only as fever and candid- uria1. In acute healthcare settings, diagnosing and managing candiduria present challenges due to the lack of reliable tests to differentiate between infection and colonization. The In- fectious Diseases Society of America provides guidelines for the management of candiduria, based primarily on expert opinions and anecdotal reports. Fluconazole is recommended as the preferred treatment unless resistance is present or the patient has renal impairments2,3. However, the emergence of several rare non-albicans Candida (NAC) species, such as Candida auris, Candida lusitaniae, C. kefyr, C. metapsilosis, C. ciferrii, and C. utilis in urine samples, poses a challenge to the efficacy of empirical fluconazole treatment, given their intrinsic resistance or susceptibility only to high doses. Candida ciferrii, though isolated in small numbers in various human infections, has consistently shown resistance to fluconazole as per the literature worldwide. Candida auris is a multidrug-resistant pathogen with limited treatment options4-8.

This study aims to assess the prevalence of UTIs caused by Candida spp. in a tertiary care center in Western Maharashtra. Additionally, it aims to identify any shifts in epidemiological trends among patients in acute healthcare settings, focusing on susceptibility patterns, with a special emphasis on UTIs caused by rare Candida uropathogens.

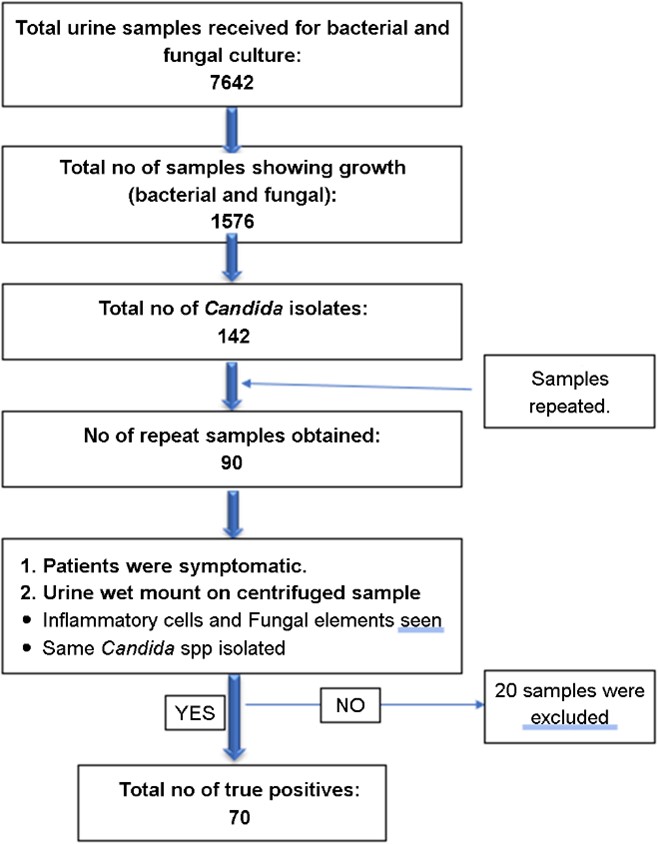

This observational, cross-sectional study was conducted at the Department of Microbiology in a tertiary care center located in Pune, India, from 01 Jun 2022 to 31 May 2023. The inclusion criteria encompassed all urine samples exhibiting Candida spp. growth, as shown in Fig. 1. To eliminate the possibility of contamination and colonization, fresh samples were obtained and processed on the same day. For the cathe-terized patients, repeat samples were obtained post-catheter change. All patients were suspected cases of urinary tract infections.

Suspected UTI: defined as any patient admitted in acute healthcare settings.

1. With symptoms of increased frequency of urination, dysuria, cloudy urine, and abdominal pain or

2. Unexplained fever in an already catheterized patient with/without increased urine output and raised WBC count

Exclusion criteria: asymptomatic candiduria patients.

Sample collection: as per the standard protocol, urine speci- mens were collected in 50 mL sterile universal containers from both catheterized and non-catheterized patients. All samples were promptly transported to the laboratory, and processing commenced within one hour of collection9.

Sample processing: all samples were inoculated on Cysteine Lactose Electrolyte Deficient (CLED) agar and incubated at 37℃ for 14~16 h. Following culture inoculation, a urine wet mount preparation was prepared after centrifugation at 3,000 rpm for 15 min to check for pus cells, RBCs, casts, and fungal elements. The growth on CLED was confirmed via gram staining (budding yeast-like cells) and subjected to further analysis using VITEK MS and VITEK 2 Compact. AFST was performed in accordance with the Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines (CLSI M27M44S 3rd edition)10.

1. VITEK MS (MALDI-TOF MS) identification11

The isolates were identified using VITEK MS (bioMerieux SA, France) as per the MALDI-TOF MS principle. The isolates were smeared onto the sample spots on the target slide, and 1 μL VITEK MS-CHCA matrix was applied over the sample and air-dried until both the matrix and sample co-crystallized. This was followed by the addition of 1 μL formic acid and air-drying. The target slide was loaded into the VITEK MS system to acquire the mass spectra, and data were compared with known mass spectra contained in the comprehensive database.

2. VITEK 2 susceptibility testing11

The isolates were subjected to AFST using VITEK 2 Com- pact (bioMerieux SA, France). From the overnight growth, a suspension of 1.8~2.2 McFarland was made, and 20 μL of the suspension was loaded onto the VITEK 2 AST-YS08 card. The sealed cards were incubated at 35℃ for a duration of 18 h. During the entire incubation period, data were collected at 15 min intervals, and the break point minimum inhibitory concentration values were used to categorize the Candida species into susceptible, intermediate, or resistant organisms. A total of six antifungals were included in the card, namely, fluconazole, caspofungin, voriconazole, micafungin, ampho- tericin B, and flucytosine. The CLSI M27M44S guidelines do not recommend the routine reporting of amphotericin B and echinocandins in urine samples; however, they were included in this study for statistical purposes. Quality control was done on a weekly cycle with a known standard strain of Candida.

1) Definition of rare isolates

Individually, the Candida species contributed to less than 3% of the total prevalence of Candida UTI globally. These include C. auris, Candida ciferrii, C. kefyr, C. metapsilosis, and C. utilis.

3. Statistical analysis

The data collected were entered into an MS Excel master sheet. The data were tabulated and analyzed using the Open- Epi software version 3.01 and Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 22. The categorical data were presented as numbers and percentages (%), whereas the quantitative data were presented in terms of mean and standard deviation. The categorical variables were analyzed using Pearson's chi-square test and Fisher's exact tests (when the expected count of 20% of cells is less than 5). Statistical significance was set at a p-value of < 0.05.

In a year-long observational and cross-sectional study conducted at the Department of Microbiology in a tertiary care center in Pune, India, from June 1, 2022, to May 31, 2023, a total of 7,642 urine samples were obtained, of which 1,576 exhibited growth. Of these, 142 samples tested positive for Candida spp., and a repeat sample was requested. Out of a total of 90 repeat samples obtained for repeat testing, only 70 were confirmed as true positive for Candida based on urine direct microscopy and cultural characteristics (re-isolation of the same species) (Fig. 1).

The mean age of the study participants was 54.9±23.6 years, with half of the participants (35 cases, 50%) being over 60 years old. More than two-thirds (48 cases, 68.6%) of the study participants were male and the majority of the isolates originated from medical ICU (44 cases, 62.9%), followed by medical wards (14 cases, 20%). More than half of the study participants (37 cases, 52.9%) had an indwelling urinary catheter, while 42.9% (30 cases) had one or more comorbid- ities (e.g., diabetes mellitus, hypertension, chronic liver disease, chronic kidney disease), of which 21 cases (30%) had a single comorbidity and the remaining 9 cases (12.9%) had two or more comorbidities.

Candida tropicalis (50%) was the most common type of Candida spp., followed by C. albicans, which constituted 25.7% of all cases. Other notable species include Candida parapsilosis (8.6%), Candida guilliermondii (4.3%), and C. lusitaniae (4.3%). Moreover, less common Candida spp., namely, C. ciferrii, C. kefyr, C. metapsilosis, and C. utilis, con- tributed to 2.9%, 1.4%, 1.4%, and 1.4% of all cases, re- spectively.

All the rare Candida isolates had no gender predilection, affecting males and females equally. The location of admission revealed no significant differences between rare Candida spp. and other species across various units, including acute medical ward, medical ICU, neonatal ICU, pediatric ICU, and surgical ICU, but all patients had at least one comorbidity. Candida ciferrii demonstrated a distinct pattern, showing a statistically significant association (p = 0.015) when patients had two or more comorbidities (Table 1) and pan-resistance to azoles, which was statistically significant (p-values for fluconazole (p = 0.015), voriconazole (p = 0.004), and flu- cytosine (p = 0.002)) when compared with other Candida spp. (Table 2).

|

Parameter |

Candida species |

p-value |

|

|

Candida |

Other |

||

|

Gender |

|

|

|

|

Female |

1 |

21 |

0.533 |

|

50.0% |

30.9% |

||

|

Male |

1 |

47 |

|

|

50.0% |

69.1% |

||

|

Location of admission |

|

|

|

|

Acute medical |

1 |

17 |

0.809 |

|

50.0% |

25.0% |

||

|

Medical ICU |

0 |

21 |

|

|

0.0% |

30.9% |

||

|

Neonatal ICU |

0 |

2 |

|

|

0.0% |

2.9% |

||

|

Paediatric ICU |

0 |

7 |

|

|

0.0% |

10.3% |

||

|

Surgical ICU |

1 |

21 |

|

|

50.0% |

30.9% |

||

|

Number of comorbidities |

|

|

|

|

None |

0 |

40 |

0.015 |

|

0.0% |

58.8% |

||

|

One |

0 |

21 |

|

|

0.0% |

30.9% |

||

|

Two or more |

2 |

7 |

|

|

100.0% |

10.3% |

||

|

Total |

2 |

68 |

|

|

100.0% |

100.0% |

||

|

Drug |

Candida

species |

p-value |

|

|

Candida |

Other |

||

|

Fluconazole |

|

|

|

|

Resistant |

2 |

7 |

0.015 |

|

100.0% |

10.3% |

||

|

Sensitive |

0 |

61 |

|

|

0.0% |

89.7% |

||

|

Voriconazole |

|

|

|

|

Resistant |

2 |

3 |

0.004 |

|

100.0% |

4.4% |

||

|

Sensitive |

0 |

65 |

|

|

0.0% |

95.6% |

||

|

Flucytosine |

|

|

|

|

Resistant |

2 |

2 |

0.002 |

|

100.0% |

2.9% |

||

|

Sensitive |

0 |

66 |

|

|

0.0% |

97.1% |

||

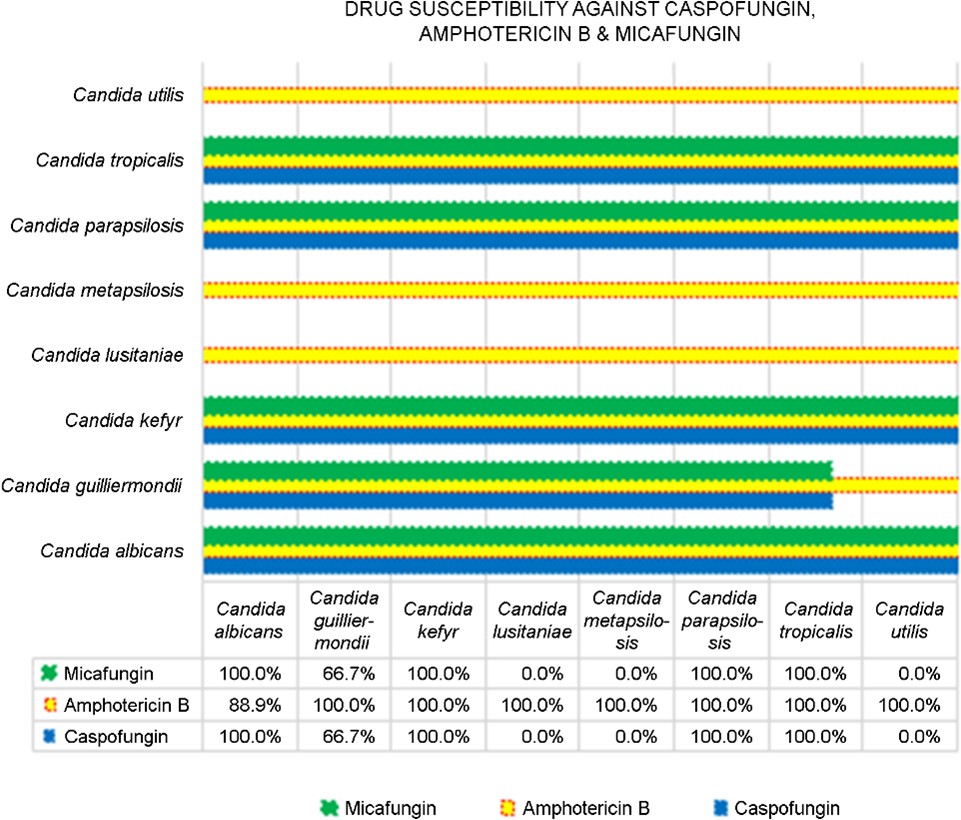

AFST was performed on all isolates with fluconazole, vori- conazole, and flucytosine. AFST with amphotericin B was conducted on 68 isolates reported by Vitek, and with caspo- fungin and micafungin on 66 isolates each. It was observed that the highest drug sensitivity was observed with ampho- tericin B (66/68 cases, 97.1%), caspofungin and micafungin (62/64 cases, 96.9%), and flucytosine (66/70 cases, 94.3%), followed by voriconazole (66/70 cases, 92.9%) and flu- conazole (87.1%). For a better representation, the six drugs have been split into commonly used antifungals, namely, azoles and flucytosine (Fig. 2), and higher antifungals, namely, echinocandins and amphotericin B.

Candida albicans has exhibited notable sensitivity, with percentages of 94.4%, 94.4%, and 100.0% for fluconazole, voriconazole, and flucytosine, respectively. Conversely, C. ciferrii showed complete resistance to all three antifungals. Candida guilliermondii showed sensitivity rates of 100.0%, 66.7%, and 66.7% for fluconazole, voriconazole, and flu- cytosine. Candida kefyr and C. utilis were 100% fully sensitive (100.0%) to all drugs. Candida parapsilosis demonstrated 100% sensitivity to flucytosine and voriconazole but suscepti- bility (83.3%) to fluconazole. Candida lusitaniae showed sus- ceptibility to voriconazole and flucytosine but resistance to fluconazole. Candida metapsilosis was susceptible to vori- conazole and resistant to fluconazole and flucytosine. Candida tropicalis showed high susceptibility, with percentages of 97.1%, 97.1%, and 100.0% for fluconazole, voriconazole, and flucytosine, respectively (Fig. 2).

Candida albicans exhibited high susceptibility to all six antifungals, with complete susceptibility of 100.0% to caspo- fungin and micafungin, and 88.9% to amphotericin B. Candida guilliermondii exhibited variable susceptibility rates, with 66.7% for caspofungin and micafungin, as well as complete susceptibility to amphotericin B. Candida kefyr, C. parapsilosis, and C. tropicalis demonstrated full susceptibility (100.0%) to all three antifungals, while C. lusitaniae and C. metapsilosis exhibited no susceptibility (0.0%) to caspofungin and micafungin. Similarly, C. utilis also showed susceptibility only to amphotericin B (Fig. 3). Furthermore, though preva- lent globally, the Candida auris and Candida glabrata species were not isolated in our study.

The Catch-22 in diagnosis

Diagnosing bacterial UTIs in symptomatic patients relies on key factors, such as pyuria and quantitative measures (CFUs /mL of urine). However, the same criteria do not apply to Candida infections. Studies have not conclusively determined the significance of pyuria or quantitative urine cultures in Candida-related UTIs. Attempting to rely on the presence of pseudohyphae in the urine proved ineffective as few Candida spp. do not produce pseudohyphae (2). The most effective approach currently available to distinguish between colon- ization and infection involves obtaining a follow-up urine sample and examining for the continued presence of yeasts. Therefore, we implemented this strategy in our study by obtaining repeat urine samples from all Candida-positive patients, coupled with assessing the presence of pus cells in urine (1 pus cell / 7 hpf), to discern between infection and colonization; all patients were symptomatic.

The overall prevalence of candiduria in acute healthcare settings worldwide

Candiduria is a concern in acute healthcare settings globally, impacting diverse patient populations, but the true global ubiquity might be subject to regional variations and healthcare practices. This study was conducted across various acute healthcare settings, i.e., acute medical ward, medical ICU, surgical ICU, pediatric ICU. Factors, such as catheterization duration, comorbidities, and healthcare facility types, contribute to its prevalence, emphasizing the need for continuous monitoring and effective management strategies. The pre- valence of various Candida species worldwide and in India is depicted in Table 312-18.

|

Study

conducted by |

Year |

Country |

Percentage |

|||

|

Candida |

Candida |

Candida |

Other |

|||

|

Alvarez-Lerma et al.12 |

2003 |

Spain |

68 |

8 |

4 |

20 |

|

Paul et al.13 |

2007 |

CMC Vellore India |

24 |

21 |

31 |

24 |

|

Achkar and Fries14 |

2010 |

USA, New York |

54 |

36 |

10 |

Nil |

|

Yashavanth et al.15 |

2010~2012 |

Mysore India |

30.3 |

9 |

45.45 |

15.25 |

|

Singla et al.16 |

2012 |

Chandigarh India |

27.27 |

50 |

18.6 |

4 |

|

Pramodhini et al.17 |

2021 |

Puducherry India |

14.3 |

7.1 |

65.7 |

12.9 |

|

Vedachalam et al.18 |

2017~2022 |

ICMR, India |

36 |

6 |

37 |

21 |

|

Our study |

2023 |

Pune India |

25.7 |

Nil |

50 |

24.3 |

|

*NAC – Non albicans Candida |

||||||

Achkar and Fries14 meta-analysis revealed that globally, C. albicans consistently dominates Candida-related urinary isolates (50~70%), followed by Candida glabrata, with C. tropicalis ranking third. They observed a rising trend in noso- comial infections associated with NAC strains. Among neo- nates, C. parapsilosis was the most prevalent type and con- sistently isolated. A multicenter study conducted in Spain revealed C. albicans as the most frequently recovered species at 68%, trailed by Candida glabrata at 8% and C. tropicalis at 4%. Interestingly, in their study, C. albicans accounted for 54% of all cases, with Candida glabrata at 36% and C. tropicalis at 10%. In contrast, their meta-analysis using Indian data revealed a shift in prevalence, with C. tropicalis (31%) surpassing C. albicans (24%) and Candida glabrata (21%) as the most common species. This discrepancy underscores regional variations in Candida epidemiology, emphasizing the need for nuanced interpretations based on geographical contexts.

Changing trends in epidemiology over the last decade in India

In our study, the prevalence of candiduria was 9%, which is not consistent with the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) data. According to the ICMR's surveillance study across 39 tertiary care hospitals from 2017 to 2022, Candida spp. constituted 20.5% of all UTIs18.

In India, studies conducted by ICMR and CMC Vellore have identified C. tropicalis as the primary cause of candiduria, which is consistent with our findings. However, in our study, a notable increase in the prevalence of C. tropicalis was observed (from 31% to 50%), with no instances of Candida glabrata detected.

Susceptibility patterns of different Candida species

In our study, the antifungal susceptibility profile of Candida isolates indicated sensitivity to all tested antifungals for C. tropicalis, C. kefyr, and C. utilis. Candida albicans demon- strated low resistance levels, with no resistance observed to echinocandins and flucytosine, 6% resistance to azoles, and 11% resistance to amphotericin B, which is consistent with the ICMR pan India report (Table 4). The ICMR report mentions Candida glabrata and C. auris had high rates of resistance (48% and 44% for fluconazole and 44% and 100% for caspofungin, respectively), but the same were not isolated in our study18.

|

Candia

albicans |

|||||

|

Study |

Year |

Azoles (Percentage) |

Echinocandins (Percentage) |

Amphotericin B (Percentage) |

Flucytosine (Percentage) |

|

Our study |

2023 |

6 |

Nil |

11.2 |

Nil |

|

Vedachalam

et al.18 |

2017~2022 Multicentric, |

7 |

6.5 |

Not reported |

Not reported |

|

Candida

tropicalis |

|||||

|

Study |

Year |

Azoles (Percentage) |

Echinocandins (Percentage) |

Amphotericin B (Percentage) |

Flucytosine (Percentage) |

|

Our

study |

2023 |

Nil |

Nil |

Nil |

Nil |

|

Vedachalam

et al.18 |

2017~2022 Multicentric, |

6.9 |

2 |

Not reported |

Not reported |

|

ICMR

- Indian Council of Medical Research |

|||||

Candida ciferrii and resistance: the impact on treatment

Candida ciferrii (Stephanoascus ciferrii) has been identified in various human infections, including endophthalmitis, intra- orbital abscess, systemic mycosis, and otitis media, in global research studies4-6. Through the sequencing of the 18S rRNA gene, umiko Ueda-Nishimura and Kozaburo Mikata cat- egorized S. ciferrii into the "S. ciferrii complex", encompassing C. ciferrii, Candida allociferrii, and Candida mucifera5. The advent of matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) has significantly improved clinical diagnosis by facilitating the identification of these rare species and guiding appropriate treatment5. All three have similar morphological and microscopic char- acteristics, but the antifungal susceptibility of these species varies. Moreover, echinocandins are the preferred treatment option for all three species. Among the azoles, no resistance against posaconazole, voriconazole, and itraconazole was reported, but fluconazole was considered resistant. Resistance is observed across the board for flucytosine5,6,19.

In our study C. ciferrii showed a distinct pattern, revealing a statistically significant association (p = 0.015) with cases having two or more comorbidities, indicating a 100% occur- rence rate. This contrasts with other species, which exhibited different distributions of comorbidity rates (Table 1). It demon- strated a distinctive drug resistance profile compared with other Candida species. Candida ciferrii showed a 100% resist- ance to fluconazole, voriconazole, and flucytosine, whereas other Candida species showed lower resistance rates (10.3%, 4.4%, and 2.9%, respectively). The p-values for fluconazole (p = 0.015), voriconazole (p = 0.004), and flucytosine (p = 0.002) indicate statistically significant differences in drug resistance between C. ciferrii and other species (Table 2). Drug susceptibility testing against caspofungin, amphotericin B, and micafungin was not reported by VITEK 2 Compact19.

Candida UTIs are on the rise in acute healthcare settings and pose challenges due to the absence of standardized criteria for diagnosis and management. Resistance trends in India have been changing with more fluconazole-resistant Candida strains being frequently isolated, emphasizing the importance of specific therapeutic strategies based on cul- ture and sensitivity reports. Candida ciferrii exhibits distinctive resistance patterns, requiring vigilant management, particularly due to its association with comorbidities.

Regular monitoring and adjustment of empirical therapy based on ongoing surveillance are essential to adapt to the changing epidemiological trends of Candida and ensure effective management.

References

1. Sobel JD, Fisher JF, Kauffman CA, Newman CA. Candida Urinary Tract Infections—Epidemiology. Clin Infect Dis 2011;52(Suppl_6):S433-436

Google Scholar

2. Kauffman CA. Candiduria. Clin Infect Dis 2005;41 (Suppl_6):S371-376

3. Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes DR, Clancy CJ, Marr KA, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of candidiasis: 2016 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2016;162:e1-50

Google Scholar

4. Paul N, Mathai E, Abraham OC, Mathai D. Emerging microbiological trends in candiduria. Clin Infect Dis 2004; 39:1743-1744

Google Scholar

5. Guo P, Wu Z, Liu P, Chen Y, Liao K, Peng Y, et al. Identification and antifungal susceptibility analysis of Stephanoascus ciferrii complex species isolated from patients with chronic suppurative otitis media. Front Microbiol 2021;12:680060

Google Scholar

6. Soki H, Nagase Y, Yamazaki K, Oda T, Kikuchi K. Isolation of the yeast-like fungus Stephanoascus ciferrii by culturing the aural discharge of a patient with intractable otitis media. Case report. Kansenshogaku Zasshi 2010;84:210-212

Google Scholar

7. Danielescu C, Cantemir A, Chiselita D. Successful treatment of fungal endophthalmitis using intravitreal caspofungin. Arq Bras Oftalmol 2017;80:196-198

Google Scholar

8. Ueda-Nishimura K, Mikata K. Species distinction of the ascomycetous heterothallic yeast-like fungus Stephano-ascus ciferrii complex: description of Candida allociferrii sp. nov. and reinstatement of Candida mucifera Kocková-Kratochvílová et Sláviková. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2002; 52:463-471

Google Scholar

9. Koneman EW, Color atlas & textbook of diagnostic microbiology. 7th Edition, Lippin-cott-Raven Koneman EW, Philadelphia, 2006

Google Scholar

10. CLSI. Performance Standards for Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Yeasts, 3rd Edition. CLSI M27M44S. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2022

11. Namaji MA, Bhat MA, Dixit M, Singh SP, Huchchannavar R. Antibacterial susceptibility pattern of S. maltophilia isolates at a tertiary care hospital, India. J Pure Appl Microbiol 2023;17

Google Scholar

12. Alvarez-Lerma F, Nolla-Salas J, León C, Palomar M, Jordá R, Carrasco N, et al. Candiduria in critically ill patients admitted to intensive care medical units. Intensive Care Med 2003;29:1069-1076

Google Scholar

13. Paul N, Mathai E, Abraham OC, Michael JS, Mathai D. Factors associated with candiduria and related mortality. J Inf 2007;55:450-455

Google Scholar

14. Achkar JM, Fries BC. Candida infections of the genito- urinary tract. Clin Microbiol Rev 2010;23:253-273

Google Scholar

15. Yashavanth R, Shiju MP, Bhaskar UA, Ronald R, Anita KB. Candiduria: prevalence and trends in antifungal suscepti- bility in a tertiary care hospital of Mangalore. J Clin Diag Res 2013;7:2459-2461

Google Scholar

16. Singla N, Gulati N, Kaistha N, Chander J. Candida colon- ization in urine samples of ICU patients: determination of etiology, antifungal susceptibility testing and evaluation of associated risk factors. Mycopathologia 2012;174: 149-155

Google Scholar

17. Pramodhini S, Srirangaraj S, Easow JM. Candiduria—study of virulence factors and its antifungal susceptibility pattern in tertiary care hospital. J Lab Physicians 2021; 13:231-237

Google Scholar

18. Vedachalam SK, Thakur AK, Parveen R, Puraswani M, Srivastav S, Ningombam A, et al. P25 Healthcare asso- ciated candiduria in ICU patients: experience from a surveillance network in India, 2017-22. JAC Antimicrob Resist 2023;5(Suppl_3):dlad077.029

Google Scholar

19. Pérez-Hansen A, Lass-Flörl C, Lackner M. Rare Yeast Study Group. Antifungal susceptibility profiles of rare ascomycetous yeasts. J Antimicrob Chemother 2019;74: 2649-2656

Google Scholar

Congratulatory MessageClick here!