pISSN : 3058-423X eISSN: 3058-4302

Open Access, Peer-reviewed

pISSN : 3058-423X eISSN: 3058-4302

Open Access, Peer-reviewed

Dong-Wha Yoo,Kyung-Deok Park,Hyeok-Jin Kwon,Jeong-Wan Seo,Jung-Ho Yoon,Ki-Ho Kim

10.17966/JMI.2023.28.1.10 Epub 2023 April 05

Abstract

Oral candidiasis, a common fungal infection in humans, is characterized by the overgrowth of Candida species in the superficial oral epithelial mucosa. The condition is associated with multiple risk factors, including impaired salivary gland function, oral mucosal damage, and long-term antibiotic or corticosteroid use. Several treatment options are available; nystatin and amphotericin B are the most widely used local medications. Recently, fluconazole has emerged as the preferred systemic treatment. We report a case of oral candidiasis in an 83-year-old male diagnosed with bullous pemphigoid in 2017 and previously administered methylprednisolone. He developed oral candidiasis a few months before presentation and was treated with 10 mL nystatin suspension three times daily; unfortunately, the disease was recalcitrant to this treatment and his symptoms showed no improvement over two months. We discontinued nystatin in favor of fluconazole syrup (Diflucan®) administered by rinsing, then swallowing, 5 mL syrup once daily. The lesion improved after one month of treatment. This case demonstrates the efficacy of fluconazole as a primary treatment for oral candidiasis. The act of rinsing the mouth with syrup exposes the oral mucosa to drug, potentially producing a better treatment response than taking the syrup orally without rinsing.

Keywords

Fluconazole syrup Mouthrinse Nystatin suspension Oral candidiasis

Candida infections are becoming more common due to the widespread use of broad-spectrum antibiotics and cortico-steroids and the growing number of individuals with immuno-compromise1. Identifying the type of Candida infection is essential for choosing an effective treatment. Identification of predisposing factors or underlying diseases is also important for managing infections2,3. Oral candidiasis a common oppor- tunistic fungal infection of the oral cavity2. Here, we report a case of nystatin-recalcitrant oral candidiasis caused by long-term systemic steroid use and treated with a fluconazole mouthrinse.

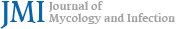

An 83-year-old male presented with a three-month history of diffuse, painful, and creamy white tongue ulcerations (Fig. 1A). He was diagnosed with bullous pemphigoid in 2017 and was being treated with ongoing, low-dose steroids.

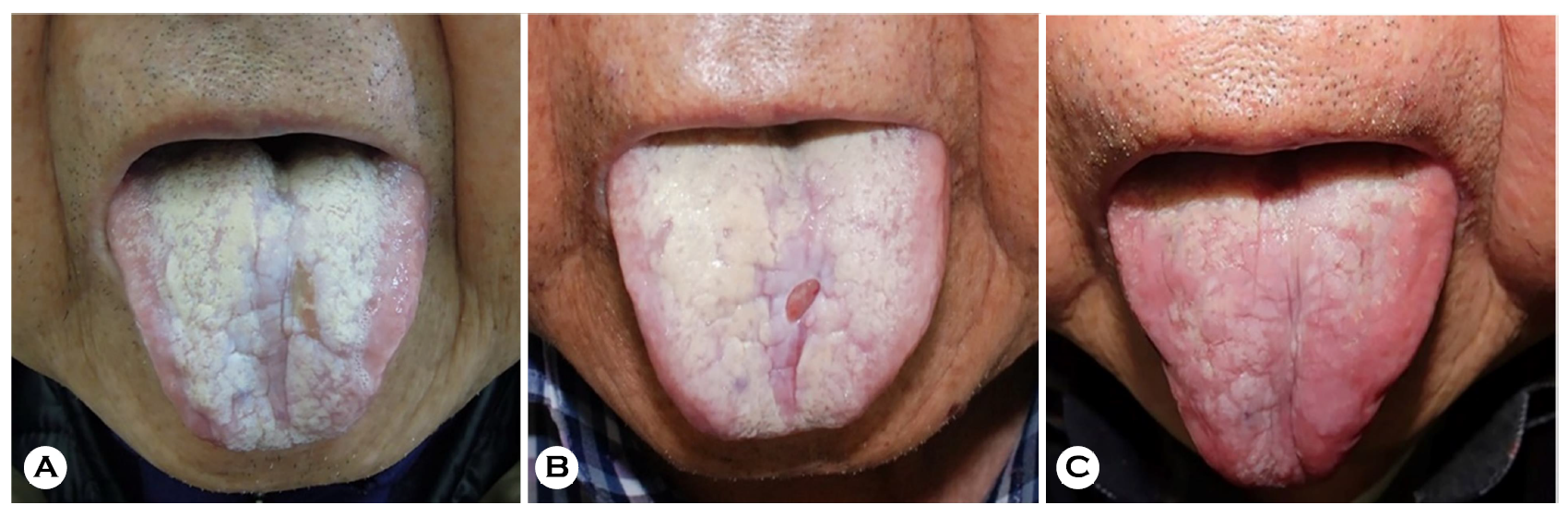

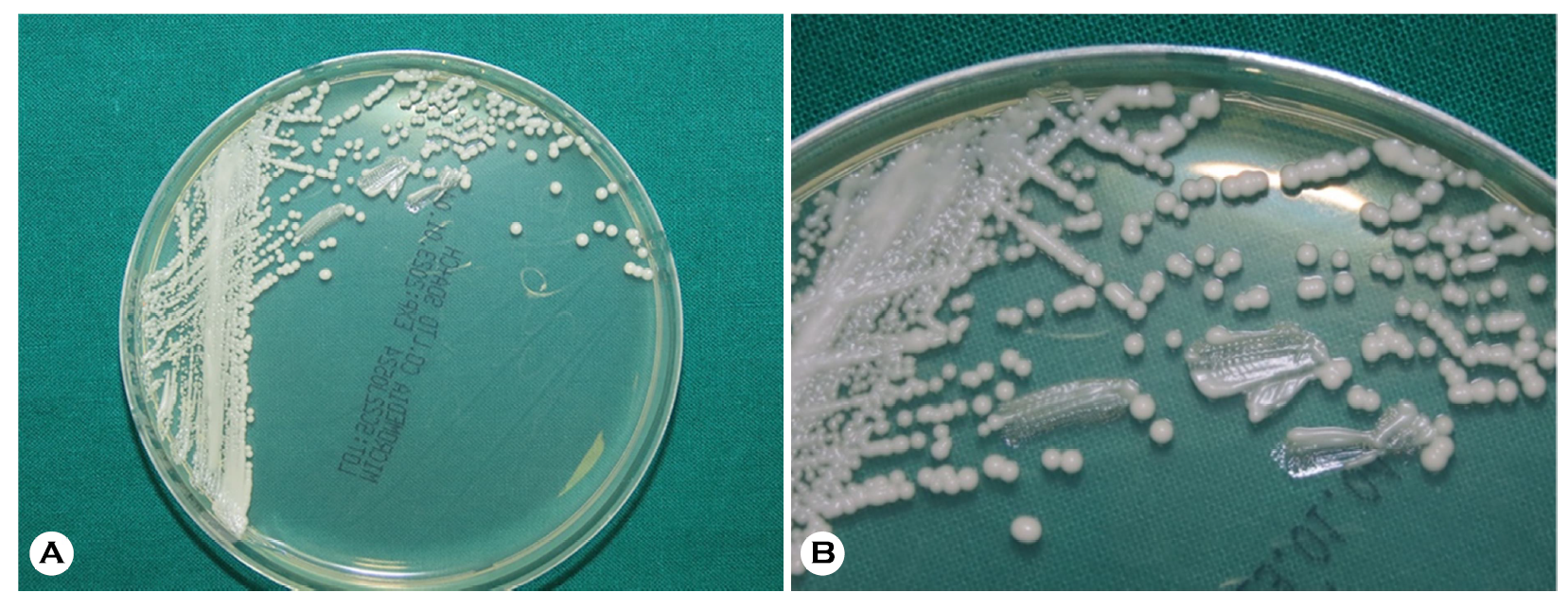

We collected a direct smear sample of the patient's oral mucosa using 10% potassium hydroxide (KOH); a fungal culture was performed on the oral lesions. The KOH smear showed numerous pseudohyphae with variably sized spores. The culture revealed smooth, creamy white colonies on Sabouraud dextrose agar plates, suggesting oral candidiasis (Fig. 2). Species identification was performed by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectro- metry (bioMérieux Vitek, Durham, NC, USA) which indicated Candida albicans on the peptide mass fingerprinting (Fig. 3).

We treated the patient with 1,000,000 IU/10 mL of nystatin suspension three times daily with the instructions to hold the suspension in the mouth as long as possible, and then swallow. After two months of treatment, the patient's symp- toms were unimproved (Fig. 1B). We therefore discontinued the nystatin suspension and, instead, administered fluconazole syrup (Diflucan®) prepared as 10 mg/mL of fluconazole in distilled water. The patient was instructed to rinse his mouth daily with 5 mL syrup for 3 min before swallowing to increase the duration of contact between the oral mucosa and medi- cated syrup. After one month of treatment, the patient's oral lesions were significantly improved. No recurrence was noted over six months of follow-up (Fig. 1C).

Oral candidiasis is caused by approximately 150 Candida species; Candida albicans being the most frequently isolated3. Recent increases in oral candidiasis in elderly patients5 have been attributed to aging of the general population. With age, the risk of candidiasis increases and its consequences become more-severe; therefore, accurate and early diagnosis is essential.

Treatment selection should be guided by the identification and management of predisposing factors or other underlying diseases. Additionally, drug-related efficacy and toxicity should be considered after determining the type of Candida in- fection2. Clinically, treatment is generally guided by the type of oral candidiasis—such as acute pseudomembranous, acute erythematous (atopic), chronic pseudomembranous, chronic erythematous, chronic hyperplastic, median rhomboid glossitis, and angular cheilitis4. The pseudomembranous type (thrush) is the classic form of the disease, accounting for nearly a third of all reported cases. Our patient was also diagnosed with pseudomembranous candidiasis, characterized by creamy yellowish-white oral mucosal plaques that, when removed with a swab, will reveal an erythematous and often bleeding underlying lesion4,6.

Several topical and systemic agents are used to treat oral candidiasis. Topical therapies—nystatin, amphotericin B, mico- nazole, or clotrimazole—are generally effective for treating superficial infections and are recommended as first-line treatments for uncomplicated oral candidiasis4,6. Nystatin (discovered in 1950 and approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration in 1954) is a membrane-active polyene macrolide with broad-spectrum anti-yeast effects. However, given its toxicity and insolubility in the gastrointest- inal tract, nystatin is mainly used in topical formulations7-10.

Systemic treatment is considered for more-severe or spreading lesions unable to be resolved by topical means alone. Fluconazole is recommended as a first-line systemic therapy and is a common antifungal agent11; however, other triazoles are available for fluconazole-resistent lesions. Fluconazole is a selective inhibitor of CYP-dependent C-14-α sterol de- methylase, which inhibits the synthesis of ergosterol and disrupts fungal cell membrane integrity. It has >90% oral bioavailability and is mainly excreted in urine. Once administered, fluconazole easily penetrates the skin, maintaining a higher concentration in the skin than in serum4,8. When administered in tablet form, fluconazole is detectable in saliva for 2 h; however, rinsing with fluconazole syrup before swallowing directly exposes the oral mucosa to the drug, which is detectable 4 h later, suggesting improved efficacy. Furthermore, because pathogenic microorganisms are usually detected in the superficial mucosa, the effectiveness of fluconazole mouthrinse might be attributable to the tem- porarily exposure of the oral mucosa to highly concentrated medicine. Additionally, the liquid suspension formulation is better for use with patients, as dry mouth and swallowing issues are more common in the elderly6,12.

Nystatin suspension, held in the mouth for as long as possible before swallowing, may exert direct and systemic effects, like the fluconazole mouthrinse. However, prior literature indicates that nystatin is non-superior to fluconazole7,10. This seems to agree with our case, who failed to benefit from two months of treatment with nystatin, but who demonstrated considerable improvement once switched to a fluconazole mouthrinse. These results provide further support for fluco- nazole's superior treatment effects when compared to nystatin in patients with oral candidiasis. Moreover, treatment efficacy appeared to be enhanced by the act of mouth rinsing. Given that a once-a-day mouthrinse is less burdensome that the nystatin suspension administered three times daily, treatment compliance may be enhanced. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first South Korean case to compare a nystatin suspension and fluconazole mouthrinse for treatment of oral candidiasis, with particular attention to the rinse's topical effects.

References

1. Neppelenbroek KH, Seó RS, Urban VM, Silva S, Dovigo LN, Jorge JH, et al. Identification of Candida species in the clinical laboratory: a review of conventional, commercial, and molecular techniques. Oral Dis 2014;20:329-344

Google Scholar

2. Garcia-Cuesta C, Sarrion-Pérez MG, Bagán JV. Current treatment of oral candidiasis: A literature review. J Clin Exp Dent 2014;6:e576-e582

Google Scholar

3. Singh A, Verma R, Murray A, Agrawal A. Oral candidiasis: An overview. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol 2014;18(Suppl 1): S81-S85

Google Scholar

4. Akpan A, Morgan R. Oral candidiasis. Postgrad Med J 2002;78:455-459

Google Scholar

5. Sakaguchi H. Treatment and prevention of oral Candidiasis in elderly patients. Med Mycol J 2017;58:J43-J49

6. Epstein JB, Gorsky M, Caldwell J. Fluconazole mouthrinses for oral candidiasis in postirradiation, transplant, and other patients. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2002;93:671-675

Google Scholar

7. Lyu X, Zhao C, Yan ZM, Hua H. Efficacy of nystatin for the treatment of oral candidiasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Des Devel Ther 2016;10:1161-1171

Google Scholar

8. Kaur IP, Kakkar S. Topical delivery of antifungal agents. Expert Opin Drug Deliv 2010;7:1303-1327

Google Scholar

9. Wong SSW, Samaranayake LP, Seneviratne CJ. In pursuit of the ideal antifungal agent for Candida infections: high-throughput screening of small molecules. Drug Discov Today 2014;19:1721-1730

Google Scholar

10. Goins RA, Ascher D, Waecker N, Arnold J, Moorefield E. Comparison of fluconazole and nystatin oral suspensions for treatment of oral candidiasis in infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2002;21:1165-1167

Google Scholar

11. Shin JH, Won EJ, Kim SH, Shin JH, Lee D, Lee DH, et al. A multicenter study of antifungal use and species distri- bution and antifungal susceptibilities of Candida isolates in South Korea. J Mycol Infec 2020;25:10-16

Google Scholar

12. Sholapurkar AA, Pai KM, Rao S. Comparison of efficacy of fluconazole mouthrinse and clotrimazole mouthpaint in the treatment of oral candidiasis. Aust Dent J 2009; 54:341-346

Google Scholar

Congratulatory MessageClick here!