pISSN : 3058-423X eISSN: 3058-4302

Open Access, Peer-reviewed

pISSN : 3058-423X eISSN: 3058-4302

Open Access, Peer-reviewed

Jihyun Hwang,Jisoo Kim,Jisung Kim,Taekwoon Kim,Jong Soo Choi,Jayoung Kim,Joonsoo Park

10.17966/JMI.2024.29.1.29 Epub 2024 March 28

Abstract

Purpureocillium lilacinum, previously known as Paecilomyces lilacinus, is a saprophytic fungus typically found in soil and decaying vegetation. Although it is infrequently pathogenic to humans, recent reports of P. lilacinum infections, primarily affecting the skin and eyes, have shown an increase. This report details a cutaneous infection caused by P. lilacinum in an 89-year-old woman. She presented with a 3-month history of an erythematous patch and nodule on her right forearm. A skin biopsy revealed inflammation, granuloma, and fungal organisms in the dermis. Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining confirmed the presence of fungal elements. The fungal culture of the medium produced colonies with a velvety pink and brown hue. PCR testing on these cultured samples identified P. lilacinum. The patient received a 2-week course of oral itraconazole (200 mg/day), which improved her symptoms. However, ongoing antifungal treatment was necessary. Additionally, due to a recent myocardiac infarction, the patient required a statin. A MIC test was conducted to identify an antifungal drug compatible with statin therapy.

Keywords

Itraconazole Purpureocillium lilacinum Statin interaction

Purpureocillium lilacinum, formerly Paecilomyces lilacinus, is a saprophytic fungus commonly found in soil and decaying plants1. Although it is rarely pathogenic to humans, there have been a recent increases in reported cases of P. lilacinum infections1. This describes a case of deep cutaneous mycosis caused by P. lilacinum in a farmer. The intent of this work is to raise awareness about such infections, especially among immunocompetent patients, and aid in selecting appropriate antifungal agents.

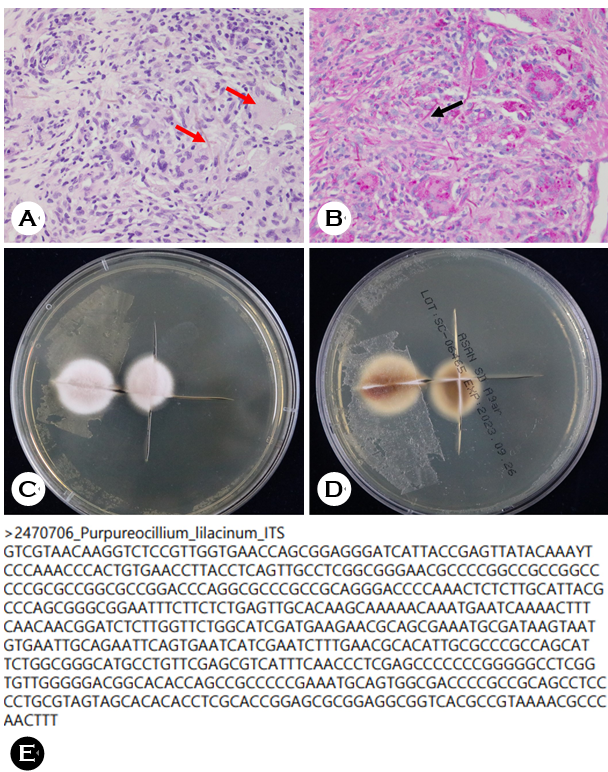

An 89-year-old woman, who worked as a farmer in a rural area, presented with a 3-month history of an erythema- tous patch and crusted nodule on her right forearm (Fig. 1) that developed after she was injured by a bamboo thorn. Initial treatment with steroids for allergic contact dermatitis worsened her symptoms. A 10% potassium hydroxide smear of a cutaneous scraping was negative. A right lower arm biopsy revealed diffuse inflammatory cell infiltration, gran- ulomatous lesions, and fungus-like organisms with H&E staining (Fig. 2-A). PAS staining was positive (Fig. 2-B), while AFB staining was negative. Gram staining, bacterial culture, and AFB culture all returned negative results.

Fungal culture on Sabouraud's medium for 1 week showed light velvet pink and white colonies (Fig. 2-C), with the reverse side brown and darker at the center (Fig. 2-D). The Department of Laboratory Medicine confirmed these find- ings. Fungal PCR testing using the MALDI-TOF MS method identified the organism as P. lilacinum (Fig. 2-E), ultimately diagnosing deep cutaneous mycosis caused by P. lilacinum. Oral itraconazole (200 mg/day for two weeks) was prescribed.

Subsequently, the patient was lost to follow-up but later admitted to the cardiology department due to NSTEMI. While her skin lesion showed significant improvement, continued antifungal treatment was necessary. Itraconazole, contra- indicated with statins and potentially leading to heart failure in some cases, necessitated MIC tests for alternative drugs. Voriconazole had the lowest MIC score (Table 1). However, as azole antifungals are contraindicated with statins, echino- candins like caspofungin or micafungin were considered suitable alternatives, pending P. lilacinum detection; however, the patient was lost to follow-up.

|

Anti-fungal agent |

Minimum inhibitory |

|

Amphotericin

B |

>16 |

|

Anidulafungin |

>4 |

|

Caspofungin |

>4 |

|

Flucytosine |

>64 |

|

Fluconazole |

>64 |

|

Itraconazole |

>16 |

|

Micafungin |

>4 |

|

Posaconazole |

>16 |

|

Voriconazole |

>0.5 |

P. lilacinum, a saprophytic fungus typically found in soil and decaying plants, is rarely pathogenic to humans. However, there has been a recent uptick in P. lilacinum infections, predominantly affecting the skin and eyes. Skin infections manifest as patches, plaques, vesicles, pustules, nodules, and crusts, often accompanied by pain, pruritus, and tenderness. These lesions frequently occur in exposed areas like the face, arms, and legs, typically linked to trauma.

Immunosuppressive conditions such as diabetes mellitus, transplantation, malignancy, and the use of immunosuppressive drugs are known risk factors for P. lilacinum infection. However, soil exposure, trauma, and an agricultural lifestyle can also be risk factors in immunocompetent hosts. Several cases among farmers have been reported in Korea2,3.

Diagnosis of P. lilacinum considers the patient's history, symptoms, clinical features, and occupational background. Diagnosis is primarily confirmed through culture results and microscopic findings. When cultured on Sabouraud's dextrose agar, P. lilacinum colonies grow rapidly within 14 days. While they initially appear white, over time they turn to shades of white to vinaceous or velvet pink with shallow wrinkles. The reverse side may display a vinaceous color but can also be brown or dark brown. To rule out contamination, recom- mendations are to culture samples in at least two media and comparing the results. Common biopsy findings include inflammation, granuloma, and fungal organisms. Molecular approaches, such as small subunit ribosomal sequence analysis, aid in more accurate fungal identification.

There is no consensus on empirical antifungal drugs for P. lilacinum infection; therefore, conducting a MIC test is advisable. Treatments include surgical debridement and systemic antifungal agents. However, the lack of established treatment guidelines underscores the importance of relevant case reports (Table 2). In many cases, Amphotericin B, flucytosine, and fluconazole have shown high resistance4. Itraconazole, despite its varied MIC values is commonly administered, and most patients improve clinically. Azole antifungals were initially used in this case, leading to clinical improvement; however, her recovery was incomplete. Due to drug–drug interactions with statins, echinocandin therapy, such as caspofungin or micafungin, was considered. Despite being lost to follow-up; this case provides valuable insights for future treatment of P. lilacinum infections in patients with cardiovascular condi- tions. Posaconazole and voriconazole—showing the lowest MIC in many cases—should be considered for cases unrespon- sive to itraconazole. There have been successful reports of treating P. lilacinum skin infections with voriconazole9,13.

|

Authors |

Age/Sex |

Symptoms |

Risk factors |

Treatment |

|

Cho

et al.5 |

19/M |

Cheek: Erythematous patch |

- |

Griseofulvin, |

|

Shin

et al.6 |

46/M |

Forearm: Erythematous nodules |

Renal transplantation |

Excision |

|

Ko

et al.7 |

83/M |

Wrist: Erythematous plaque |

Farmer |

Itraconazole |

|

Hwang

et al.8 |

81/M |

Hand: Erythematous plaque and pustules |

- |

Itraconazole |

|

Jung

et al.9 |

72/M |

Shoulder: Erythematous plaque |

- |

Itraconazole → |

|

Kwak

et al.10 |

81/M |

Hand: Erythematous pustular plaque |

Farmer |

Itraconazole |

|

Ha

et al.11 |

72/F |

Forehead: Erythematous and scaly patch |

- |

Itraconazole |

|

Jung

et al.3 |

84/M |

Forearm:

Erythematous papules and patch |

Injury from farming tool |

Itraconazole |

|

Farmer |

||||

|

Jin

et al.12 |

72/F |

Forehead: Erythematous and scaly patch |

- |

Itraconazole → |

|

Present

case |

89/F |

Forearm:

Erythematous patch and nodule |

Injury from bamboo thorn |

Itraconazole |

Korean cases of P. lilacinum included lesions concentrated on exposed areas such as the face and arms, and there have been many infections in farmers2,5. Similar to this case, there were many cases of treatment starting with itraconazole and being ultimately curative14. However, there was a case in which voriconazole resulted in clinical improvement after none had been seen over 14 weeks of itraconazole administration9. In conclusion, the initial treatment should be itraconazole in patients with confirmed P. lilacinum infections. If the treatment response is unclear, it is necessary to consider switching the drug according to the MIC test. Therefore, if the MIC test is impossible, take Posaconazole or Voriconazole empirically.

References

1. Lu KL, Wang YH, Ting SW, Sun PL. Cutaneous infection caused by Purpureocillium lilacinum: Case reports and literature review of infections by Purpureocillium and Paecilomyces in Taiwan. J Dermatol 2023;50:1088-1092

Google Scholar

2. Kim HJ, Cho GJ, Kim JU, Jin WJ, Park SH, Moon SH, et al. A case of deep cutaneous Purpureocillium lilacinum fungal infection in an immunocompetent patient. J Mycol Infect 2019;24:52-57

Google Scholar

3. Jung ES, Lee SK, Lee IJ, Park J, Yun SK, Kim HU. A case of cutaneous Purpureocillium lilacinum infection. J Mycol Infect 2021;26:8-12

Google Scholar

4. Corrêa-Moreira D, de Lima Neto R, da Costa GL, de Moraes Borba C, Oliveira MME. Purpureocillium lilacinum an emergent pathogen: antifungal susceptibility of environmental and clinical strains. Lett Appl Microbiol 2022;75:45-50

Google Scholar

5. Cho GY, Choo EH, Choi GJ, Hong NS, Houh W. Facial cutaneous mycosis by Paecilomyces lilacinus. Korean J Dermatol 1984;22:89-93

Google Scholar

6. Shin SB, Lee HN, Kim SW, Park GS, Cho BK, Kim HJ. Cutaneous abscess caused by Paecilomyces lilacinus in a renal transplant patient. Korean J Dermatol 1998;3:185-189

Google Scholar

7. Ko WT, Kim SH, Suh MK, Ha GY, Kim JR. A case of localized skin infection due to Paecilomyces lilacinus. Koran J Dermatol 2007;45:930-933

Google Scholar

8. Hwang SL, Kim JI, Song KH, Cho YS, Nam GH, Park J, et al. A localized skin infection due to Paecilomyces lilacinus. Korean J Dermatol 2011;64:255

9. Jung MY, Park JH, Lee JH, Lee JH, Yang JM, Lee DY. A localized cutaneous Paecilomyces lilacinus infection treated with voriconazole. Korean J Dermatol 2013;51:833-836

Google Scholar

10. Kwak HB, Park SK, Yun SK, Kim HU, Park J. A case of localized skin infection due to Paecilomyces lilacinum. J Mycol Infect 2017;22:42-49

Google Scholar

11. Ha NG, Park KD, Bang YJ, Jun JB, Choi JS, Lee WJ. A case of cutaneous Purpureocillium lilacinum infection looking like psoriasis. J Mycol Infect 2021;26:72-76

Google Scholar

12. Kim JH, Bang YJ, Jun JB, Lee WJ. Therapeutic use of posaconazole for cutaneous Purpureocillium lilacinum infection refractory to itraconazole. J Mycol Infect 2023; 28:79-83

13. Wang Y, Bao F, Lu X, Liu H, Zhang F. Case report: cutaneous mycosis caused by Purpureocillium lilacinum. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2023;108:693-695

Google Scholar

14. Burgos-Blasco B, Gegúndez-Fernández JA, Díaz-Valle D. Purpureocillium lilacinum fungal keratitis: Confocal micro- scopy diagnosis and histopathology correlation. Med Clin (Barc) 2021;157:398-399

Google Scholar

Congratulatory MessageClick here!